One night in the early ‘90s, I was driving through the desert of Arizona on the way home from a short tour with my brother, David. Tom, our bass player and Chris, our sound man were sleeping. I had a wild idea.

I looked at my brother squarely and said, “We gotta go to Europe.”

At the time, we were a bit frustrated with where we were at in our career. It wasn’t all bad; we had great reviews, and we had two records with MCA Jazz and two with Blue Moon Records (real records with real budgets, back in the day when that still happened). But even with all of the press and airplay, we just weren’t manifesting the level of touring that I wanted. Many of my influences were on ECM, a label in Germany. I knew about the respect this kind of music earned in Europe, and I felt that was the most appropriate place to be.

Seven months after that car ride, we were there.

I think back on it now and wonder how the hell did I do that? These days, if my wife and I were to think about moving to another state, we’d be carefully making plans. But when I moved to Europe?

“Bro, pack up your stuff – we’re going!”

Sometimes you have to do what you have to do. As a musician, taking chances is part of it. You don’t want to get stuck in your comfort zone, and be fearful of stepping out or trying something different.

Before we moved, everything seemed to line up under a really peculiar set of circumstances. My mother has Dutch citizenship, but was born and raised in Indonesia. She was a POW from 1941-1945. When the war ended, she and her family left to go back to Holland. It was later that she met my American father.

We traveled all the time. We had relatives in the Netherlands and in Germany (Mom’s mom was German), and we’d visit these people quite often. So when my brother and I decided to move to Europe, we thought we’d reach out to these relatives for help. We really didn’t have a concrete plan.

But in February of 1992, I saw an advertisement at a little club where I used to host events – a hip, independent coffee shop that featured jazz music. The ad said “Dutch bass player looking for work.” I met him by chance and he had a friend who was in town visiting for two months. A week later, we started getting to know the friend and he ended up staying with us.

At one point he started saying, “Oh, you gotta come visit my city. I’m from Antwerp.” He kept throwing out this offer. As time went on, I started seriously considering it. Maybe we’ll just go there and see what the adventure leads to. He had a two-bedroom apartment above a bar in the heart of Antwerp. Between four of us, we would eventually each pay just $75 a month in rent.

We now had a place to stay, and things started to line up after that. The president of our label, Jim Snowden gave us money to ship our gear and purchased our carnet. He even bought my plane ticket. My dad worked for an airline and landed us some great deals.

We were going to fly to Brussels. My brothers and family call me ‘Bru’, and coincidentally, the tag for the Brussels airport is BRU.

I thought, cool – this is my airport.

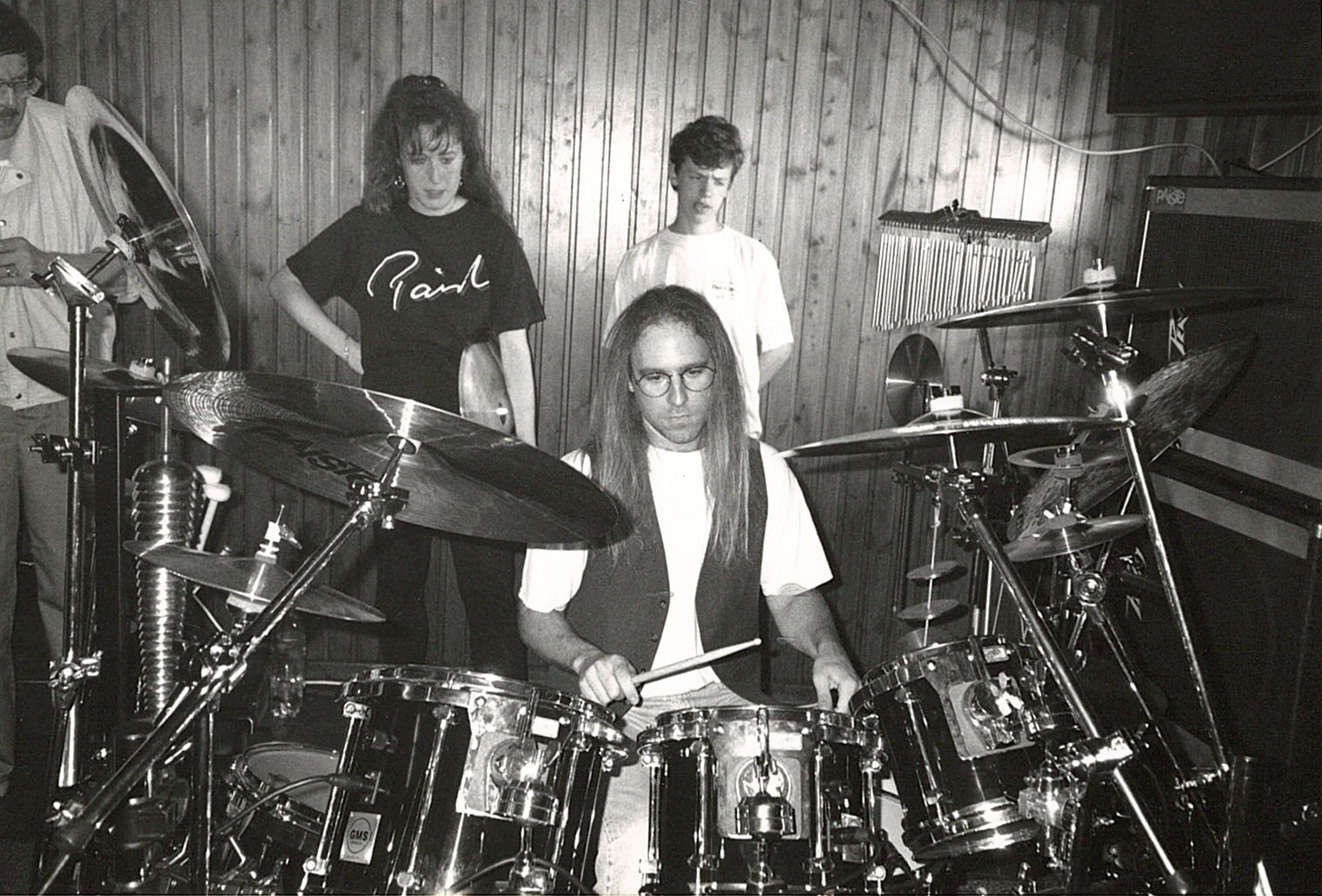

After the move, things didn’t happen quickly, but they happened. I met so many drummers I would’ve never met had I not gone to Europe: Tony Arco in Milan, René Creemers, Bruno Meeus, Jojo Mayer.

I was in this mode of traveling between Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Austria. I was asked to be the head of the drum department of the now defunct American Institute of Music, in Vienna. I had a gig with a famous organist, Barbara Dennerlein from Munich. René Creemers even brought me out to do some workshops at the Conservatory in Tilburg and the Conservatory in Arnhem (both in the Netherlands).

None of these things would have happened if I didn’t make the move. I also wouldn’t have experienced a deeper relationship with my drum teacher, Freddie Gruber.

None of these things would have happened if I hadn’t made the move.

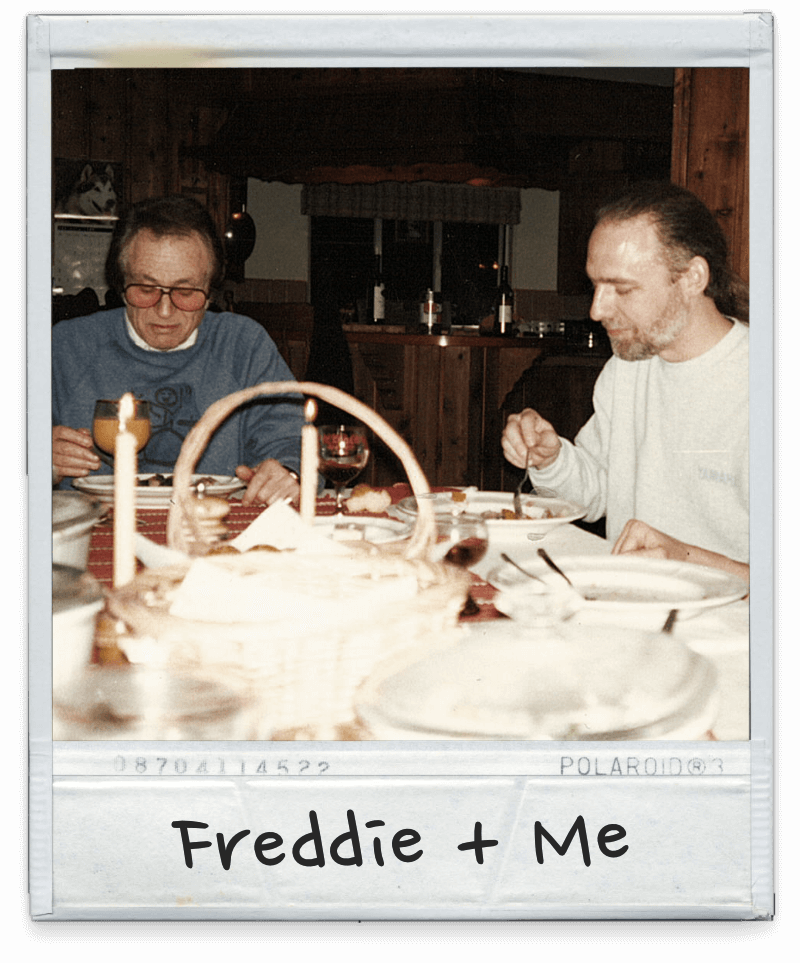

Freddie was so knocked out of his head that I was leaving Los Angeles that he was freaking out. We were close. I was his first call guy, his pick-up-food, take-to-airport, always-reliable guy. If you knew Freddie, you knew he just didn’t go anywhere. But two months after arriving in Belgium, he came to visit.

Dealing with him was always a challenging affair.

At one point, Freddie, my brother and I were driving to the DW distributor located about two-and-a-half hours from Antwerp. I knew where it was, but actually getting there by car was another story. I would get stuck on a one-way street, or go the wrong way, or have to get around a construction site. After a while, Freddie started badgering me from the back seat.

“This don’t look right, man.”

“I think you fucked up, man.”

“Do you know where you’re going, man?”

After 30 minutes, there was steam coming out of my ears. We saw a landmark park by the Rijk’s Museum. I pulled over.

“Get out of my car.”

Freddie looked at me. “What?”

“David, stay here with Freddie and I’ll be back in an hour.”

After I drove away, Freddie apparently looked at my brother and said, “Jesus Christ, David! What did your father do to Bruce?”

“The same thing your father did to you, Freddie.”

–

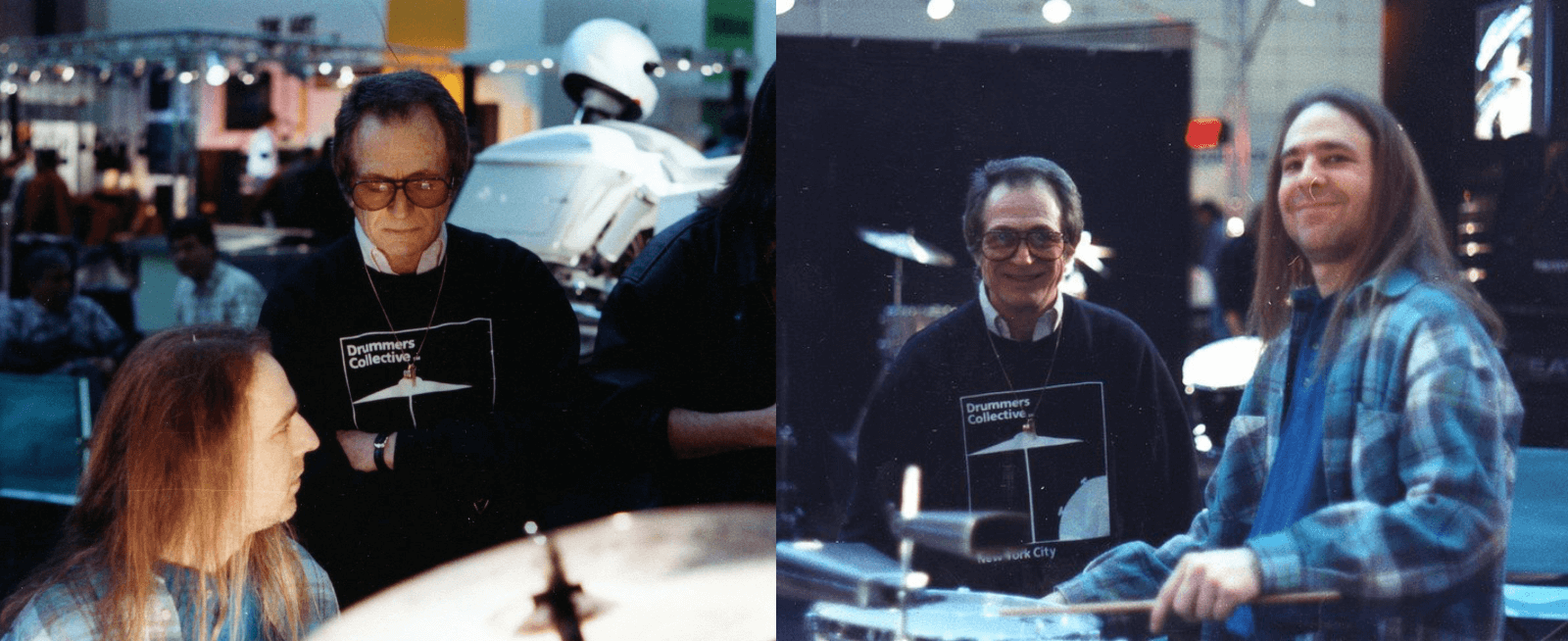

He came to visit me a few times. We would do Musikmesse in Frankfurt (basically the NAMM of Europe), and Koblenz Drum Fest. We met the guys from Drums & Percussion Magazine, Slagwerkkrant (the Dutch Drum mag), store guys, school guys. During that first trip, Freddie was having a hard time acclimating to the cultural changes. He was also upset because no one really knew who he was; it was kind of a pride thing. We did a couple of clinics together where I would play and Freddie would pontificate. He wasn’t the most focused guy, so I’d have to rein him in sometimes.

“Don’t be a fucking wise guy,” I’d warn him. “They aren’t going to get your sense of humor. Be straight up. If you’re just doing schtick, nobody is going to ‘get’ it.” On one occasion I got him to deliver – still cryptic, but his tone of voice was open and giving.

Freddie originally had plans to go to London, but he had to blow them off because he fell down my stairs and dislocated his shoulder.

We were chilling out at my place one night, listening to this Bill Evans record, Explorations. Freddie wanted to smoke some black tar hash. You take a pin and put the hash on it, and slide it through a card or something. You put a glass on it, light it, then take the glass off and inhale the smoke. It was two or three o’clock in the morning.

I said, “Freddie, I gotta go to bed. There’s a light on this side of the hall; it’s a timed light. Hit it here. On the bathroom side, hit the light outside the door so you can see where you’re going.”

Right outside of that bathroom, if you took the wrong step, you’d go straight down a narrow and steep flight of stairs.

When Freddie fell down that flight at around 4 o’clock in the morning, it woke my brother and I out of a dead sleep. “What the hell was that?”

All you could hear from the bottom of the stairs was, “Jesus Christ, goddamnit…”

We had to bring Freddie to Emergency while he was freaking out. As it turns out, he didn’t break anything, but I had to tie his sling the rest of the trip.

My brother always joked with Freddie that he spent so many days bitching, the ghost of Buddy Rich pushed him down the stairs.

–

That first time Freddie came to visit, we spent almost three weeks together. His girlfriend, Cindy joined us for the last few days. She was 30-something years his junior. They were like Alice and Ralph fighting in The Honeymooners; I had to put up with their yelling.

When the trip came to an end, I dropped them off on the curbside of Schiphol airport in Amsterdam. Freddie looked back at me like I was a father leaving my kid at summer camp.

“Who’s going to tie my sling?”

I said, “You have Cindy.”

“She can’t do anything,” he grumbled.

“Bye, Freddie!”

I lived in Europe from ‘92 to ‘97. Part of that journey opened my eyes to a much larger landscape of the drumming and educational community. I saw how much interconnectivity there was, even before the internet became popular.

Following an idea on a whim was monumental in my life, not only as a player, but as an educator. I had a better flavor for how it all works. I’d come back to America and guys would say “How do you do that?” and I’d try to explain, but everyone has their own journey.

If you’re a musician sitting back and waiting for the perfect scenario, it ain’t gonna happen. Go and take chances. Think about where you want to go, and just go and do it. If you want to become successful, it’s all about laying it on the line. Have a vision of what you want to do, and don’t worry about going in order from steps 1-4. You might have to do step 4, then step 2. There’s no straight line.

You don’t think; you just do it.

If you’re open to the experience, I think things will line up for you. If I were to sit back now and calculate going to Europe and doing it the way I did, it would never happen. I’d be frozen in fear. No one was going to bring me to Europe. Maybe if I’d waited, but I don’t think so. It’s hard to say. I said “I gotta do this”, and got it together.

Sometimes you have an idea, and you just beeline it. You don’t think; you just do it.

Look at Arnold Schwarzenegger. Think about the odds he had. A bodybuilder with a thick Austrian accent? Look at what he achieved as an actor in America.

Whether it’s putting together a project or taking an opportunity, don’t think about how hard it’s going to be. Just start doing it. Make the steps. You know no one is going to do it for you.

Right?

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »