Are you starting to play drums and want to learn how to read music? Maybe you’ve been drumming for years but you’ve been too intimidated to give it a try. Whether it’s a concert score or AC/DC PDFs, this guide will teach you the basics of reading and writing drum notation from the first quarter note to the final cymbal crash.

This article will teach you several ways to notate drum music and includes multiple formatting styles. Because notation isn’t 100% standardized, rhythms may be presented differently from one drum book or lesson to another. It’s better to be prepared for anything!

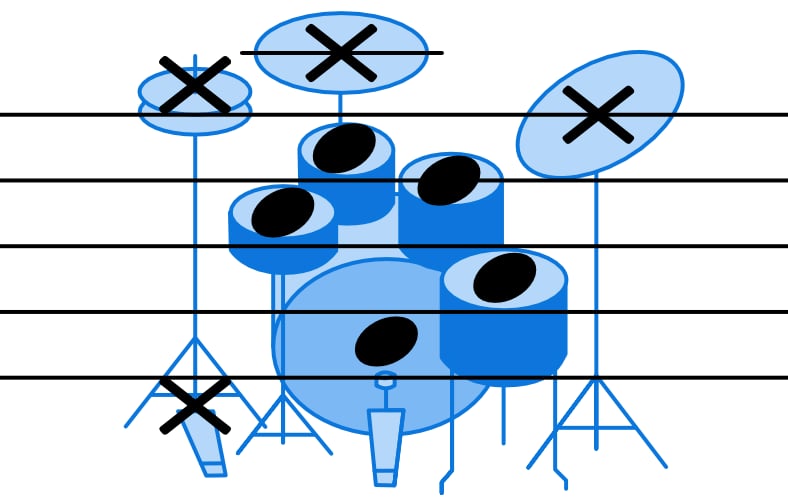

Drum notation has a lot in common with the notation for other instruments since it’s laid out on a set of five horizontal lines (called a “staff”). Each part of the drum set is written on a line – or in the space between the lines – so you can visually tell everything apart.

Lower pitches like the bass drum and floor tom are towards the bottom of the staff, while the snare and toms are in the middle. Higher tones like cymbals are at the top.

This graphic – known as a ‘drum key’ – shows where the most common parts of the drum set appear on the staff. It all makes sense when you look at it!

For example, the hi-hat is both at the top (when you hit it with your stick) and the bottom (when you step on it).

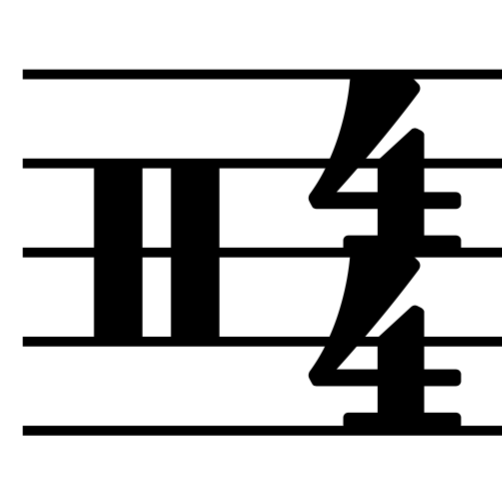

The two vertical boxes on the left are called the “drum clef,” which tells us that this music is specifically for drums. It’s just like the treble and bass clefs you’ll see in notation for melodic instruments.

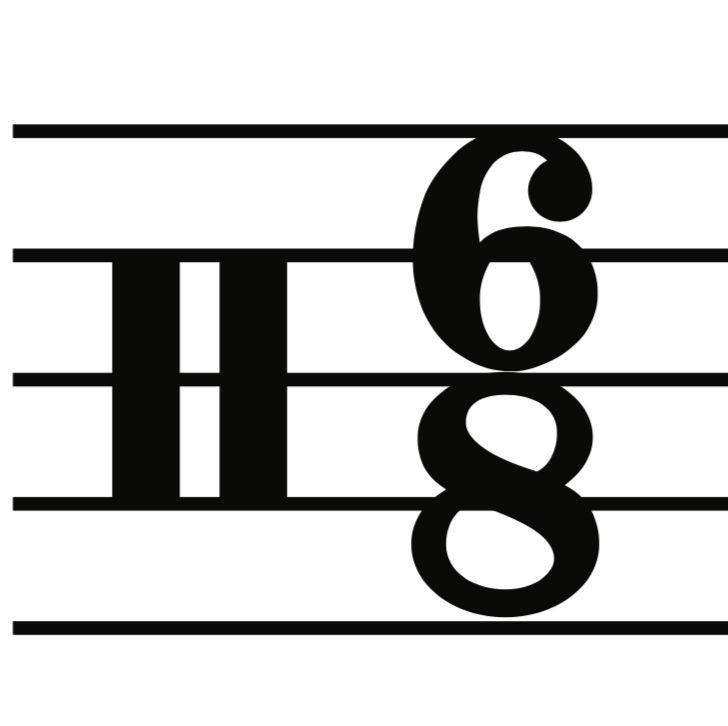

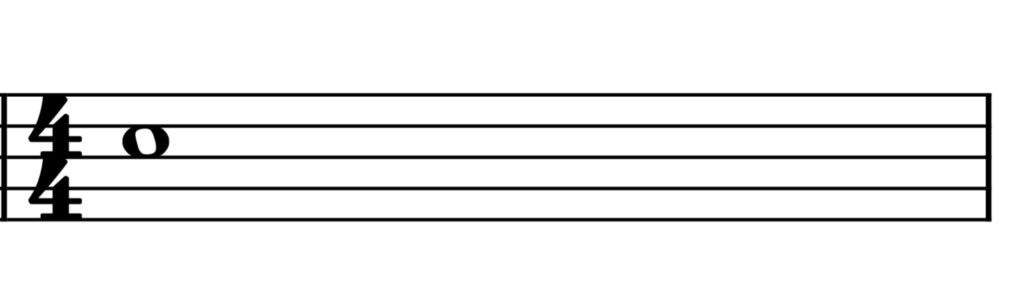

This is one of the first things you should look for when you see a drum chart. The time signature is the two numbers stacked on top of each other on the left side of the staff.

Written music is divided into chunks called measures. Think of a measure (or “bar”) as a pie. Every measure has a certain number of counts or “beats” in it, which make up fractions of the whole pie.

In the time signature, the top number tells you how many beats are in each measure. The bottom number tells you the value of each beat. For example, 4/4 time has 4 beats per measure and each beat is worth one quarter note. 6/8 time has 6 beats per measure but each beat is worth one eighth note.

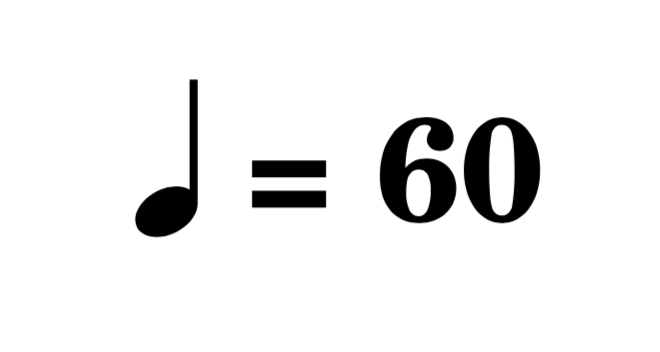

It’s also important to check out the tempo or “beats per minute” at the top left of your chart. A tempo of 60 beats per minute (BPM) in 4/4 time means that each of the measure’s four quarter notes occur once per second (just like the second hand of a clock).

Now that you know the basics of the staff, time signature and tempo, it’s time to check out some drum notation!

Let’s start at the top. Cymbals and hi-hat notes are usually written as an ‘x’ while drums are written as solid round notes.

Here are some of most common note values you’ll encounter and their value in 4/4 time:

Adding an additional ‘slash’ to the stem of a note cuts its value in half.

Placing a small dot to the right of any of these notes adds an extra 50 percent of the note’s value. For example, if a quarter note is worth 1 beat, a dotted quarter note is worth 1.5 beats.

Multiple notes that comprise a beat are often connected by horizontal lines called “beams” to make them easier to group visually.

A curved beam or “tie” connecting two notes means that you play them as if they are one note. The second note is silent and its value is added to the first. For example, if there is a cymbal hit on the “and” of beat 4, it is written as a tied note across the bar line to show its longer sustain.

Triplets are made up of three notes equally spaced over a period of time where there would normally be two notes. They’re connected by a horizontal beam and written with a small ‘3’ above them.

Triplets are the most common type of “tuplet” (which is any equal subdivision of notes spaced evenly over a larger note length).

You may also notice the stems of the notes (the straight vertical lines jutting out). In traditional drum notation, notes played with the feet have downward-facing stems, while everything else points upward. This shows you the separation of the hands and feet (and isolating your limbs can help you learn new patterns).

The note values of the hands and feet each add up to the total number of the beats in the whole measure (for example, in 4/4 time, the notes and rests in the hands would add up to 4, and so would the notes and rests in the feet).

One thing to keep in mind about music notation is that there are a lot of minor variations in the way different people write things. Many of the rules are flexible and evolve over time. In modern drum notation, all the stems point upward (even the notes played on the bass drum) and everything looks more connected. All the notes together add up to the total number of beats in each measure.

However, it’s harder to visualize the separation of the hands and feet this way. Traditional and modern notation both have pros and cons, and it’s useful to learn how to read both styles.

A rest tells you when not to play. Here are some of the most common types in 4/4 time.

Just like with notes, adding a dot tacks on an additional 50 percent of the rest’s value. For example, here’s a dotted quarter-note rest (worth 1.5 beats):

Now that you’ve got a basic idea of how notes and rests work, let’s get into some other important symbols you might come across in different types of drum music.

If you see the letters ‘R’ and ‘L’ above or below the staff, these signify which notes should be played by your right and left hands. This pops up most commonly in educational exercises and rudiments rather than full song charts.

Accented notes should be played louder than the rest. The most common type of accent symbol is a wedge with the opening pointing left. Hand accents are usually written above the staff, while foot accents are below. Less common is a wedge with the opening pointed downward, which means the accent should be a short or “staccato” note.

These are super helpful in telling us how a note should be played. Staccato notes have a dot above them (it’s usually best to play those on a drum rather than a cymbal that rings too much).

Longer, or “legato” notes tend to be tied to visually indicate their duration. These work best if you play them on cymbals since they have more sustain.

When you see an ‘o’ sign above the hi-hat, that means you should lift your toes and open it. A plus sign means you should close the hats.

Sometimes people use curved beams to connect open and closed hi-hat notes (but sometimes they don’t…so be ready for either style!)

Loose hi-hat notes (where you should play the hi-hat partially open) are often written as an ‘x’ with a circle around them.

Notating and reading rudiments is an important part of understanding drum music. Flams and drags are types of “grace notes” which have no numerical value – you just play them immediately before another note.

“So I don’t count them as part of my pie when I add all the notes and rests in each measure?” Nope!

Think of these as little ornamentations that precede the main note they’re attached to. They’re tied to the main note with an upward-facing curved beam.

Bounced notes are written with a slash through the stem of the note. This is called a “tremolo”. One slash indicates a bounce or double stroke, and these slashes are also used to notate open rolls (where you can hear each stroke individually).

Closed rolls and buzzes (where you can’t hear each individual note) have a ‘z’ through the note’s stem.

Longer rolls of either type are written as tied notes to indicate their length. They’ll also sometimes have a number written next to the tie to tell you how many strokes are in the roll.

Along with the rests we went over earlier, here are a few other signs you might encounter in drum music.

A caesura (commonly called “railroad tracks”) is a pause marker with two leaning vertical slashes. It basically means “stop right there!”

A fermata, or “hold” is written as a downward facing semi-circle with a dot in the middle. This indicates a full pause in the music where you stop counting the time.

You may also see a pair of eyeglasses, which is an informal way to say “watch out, here comes something important!”

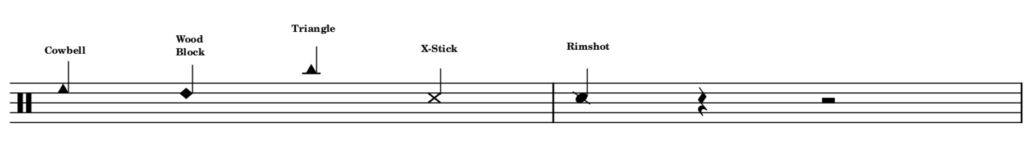

Cowbells, wood blocks, and triangles are written with triangular or diamond-shaped note-heads on different lines of the staff.

Cross-sticks are written with an ‘x’ on the snare drum line, while other types of rimshots (hitting the rim and snare together or hitting one stick with the other as it rests on the snare head) appear as a round note with a slash through it.

Stay alert and be ready for different types of notation!

Dynamic markings are some of the most important symbols on any drum chart. They help you play with sensitivity and convey important changes in the music. If you nail the dynamics on drums, everyone in the band will love you!

Here are a few of the most common dynamic markings from quietest to loudest:

ppp (triple pianississimo, sometimes called “triple-p” or “triple piano”) – This means “very, very quiet.” As quiet as you can play!

pp (pianissimo, or “double-p”) – This means “very quiet,” or just barely above ppp.

p (piano) – Quiet

mp (mezzo-piano) – Medium or moderately quiet

mf (mezzo-forte) – Medium or moderately loud, but not too loud

f (forte) – Loud

ff (fortissimo) – Very loud. We’re not quite at top volume, but we’re close!

fff (fortississimo) – Very, very, loud. This is sometimes also called “triple-forte” or “triple-f.” Now we’re in ear-spitting territory!

Along with these basic dynamic markings that tell you how loud or quiet to play, there are also a couple of important symbols that indicate changes in the dynamics.

A crescendo is a gradual increase in the volume notated with a right- facing “hairpin.” Make sure not to get too loud right away and allow the volume to build steadily.

A decrescendo (or diminuendo) is the opposite. Again, make sure not to get to your final volume too quickly. Keep an eye on the duration of the dynamic change and bring your volume down steadily. These subtle dynamic changes can make a big difference in your sound!

Along with these basics, here are a couple of other dynamic symbols that are important for drummers.

If you see the word subito (or “suddenly,” sometimes abbreviated “sub.”) before a dynamic marking, that means you’re making an abrupt change. For example, if you’ve been chugging along at ‘mf’ or ‘f’ and you see “sub. p,” bring the volume down right away.

Another similar concept uses an ‘fp,’ or fortepiano sign. This is a loud first note followed by an immediate drop in volume. You’ll often see these on the first note of a dramatic roll (think of a classic drum roll used to build tension and play vaudeville artists onstage).

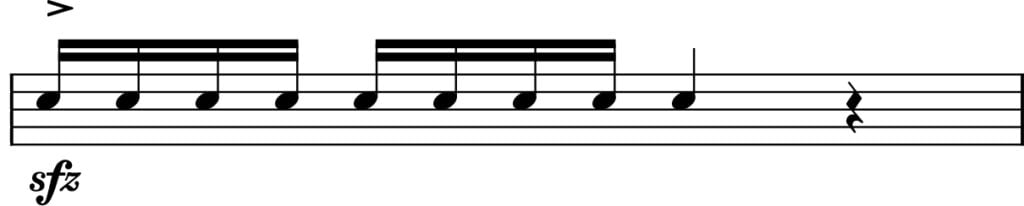

Also keep an eye out for the ‘sfz’, or sforzando symbol, which literally means “suddenly, with force.” The idea here is to emphasize the attack of a note or phrase (smack it, then go back to whatever dynamic level you were at before).

Knowing how to read the road map is the key to a successful journey through any drum chart. Here are a few of the most common directional signs you’ll come across:

There’s a lot of repetition in drum music, so you might see these a lot. A repeat is written as 2 vertical bar lines with 2 adjacent dots which signal that you should go back and play a section again.

“But where do I go back to?” Just look out for the inverted repeat sign to tell you the boundary of the repeated section. If there’s no inverted repeat signal, go back to the beginning of the chart. Repeat the section once unless otherwise indicated.

Sometimes a section of your chart will repeat, but the last bar or two is slightly different each time. First and second ending markers make the whole thing easier to read by notating these varied endings without rewriting the entire section (so you’ll ultimately have a shorter chart with fewer page turns).

The first time through, play the first ending (the measure with the “1” over it) and jump back to the inverted repeat sign. After you go through the second time, skip the first ending and jump directly to the second before you continue.

Some charts have even more than two endings, so just keep repeating until you get to the last one.

This is another way to shorten the length of a chart by jumping backward and forward so you don’t have to re-write a section that repeats. This concept can be tricky at first, but once you get it you’ll be in great shape to read any kind of drum chart.

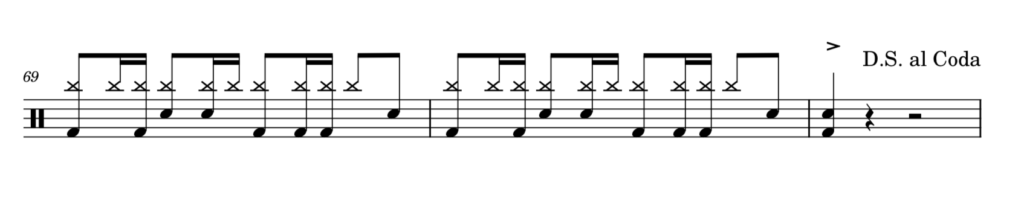

The first thing you’ll need to look out for is the ‘D.S.’ or Dal Segno, which means “from the sign.”

Think of this as a portal back to an earlier symbol in the chart (commonly called ”the sign”). It looks like an ‘S’ with a backward slash through it and two dots on either side.

A ‘D.C’., or Dal Capo is a similar concept that means “go back to the beginning” instead of to the sign. Either way, you’re jumping backward to an earlier point in the chart.

Usually, the D.S. or D.C. marker will have the words “al Coda” or “al Fine” after it. This tells us whether to play straight through to the end (“al fine”) or if we’ve got one more jump to make (“al coda”). If it’s an “al coda,” keep playing until you see a “To Coda” marker.

The Coda, which looks like a bullseye (or a circle with a plus sign in it), is our ultimate destination and the “To Coda” marker is another portal that sends us forward to get there (it’s like warping in a video game). After you leap forward to the Coda, play through to the end and collect your prize.

These pop up a lot in drum charts. Full measure repeats are written as a backward slash with 2 dots and signal that you should play whatever you played in the previous bar. Multi-measure repeats will have 2 slashes and the number of bars written above this symbol.

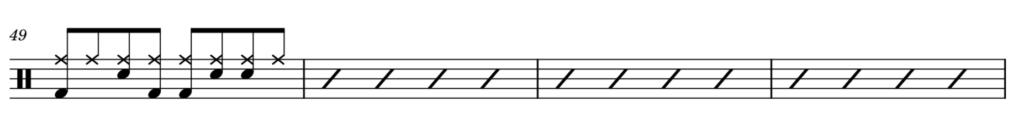

Many drum charts also use a concept called slash notation to indicate that the drummer should play time or continue grooving. This concept features crooked hash-marks on each beat of the measure instead of writing musical notation or patterns.

Compared to measure repeats, slash marks offer a bit more flexibility to vary the pattern you’re playing.

Measure numbers are landmarks that tell you how many measures into the piece you are.

Rehearsal letters normally correspond with different sections of the song. The verse could be “Letter A,” the chorus “Letter B,” etc.

Both of these types of markers are especially useful when you’re rehearsing longer pieces of music and usually appear to the left of the staff.

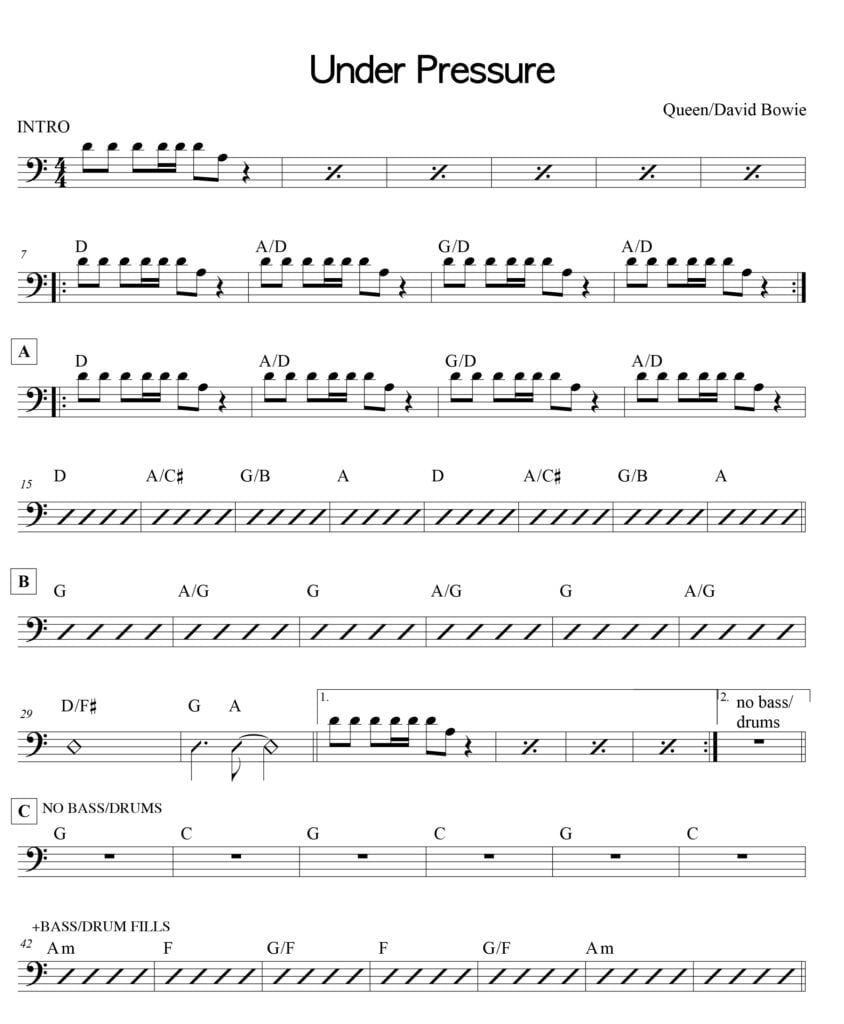

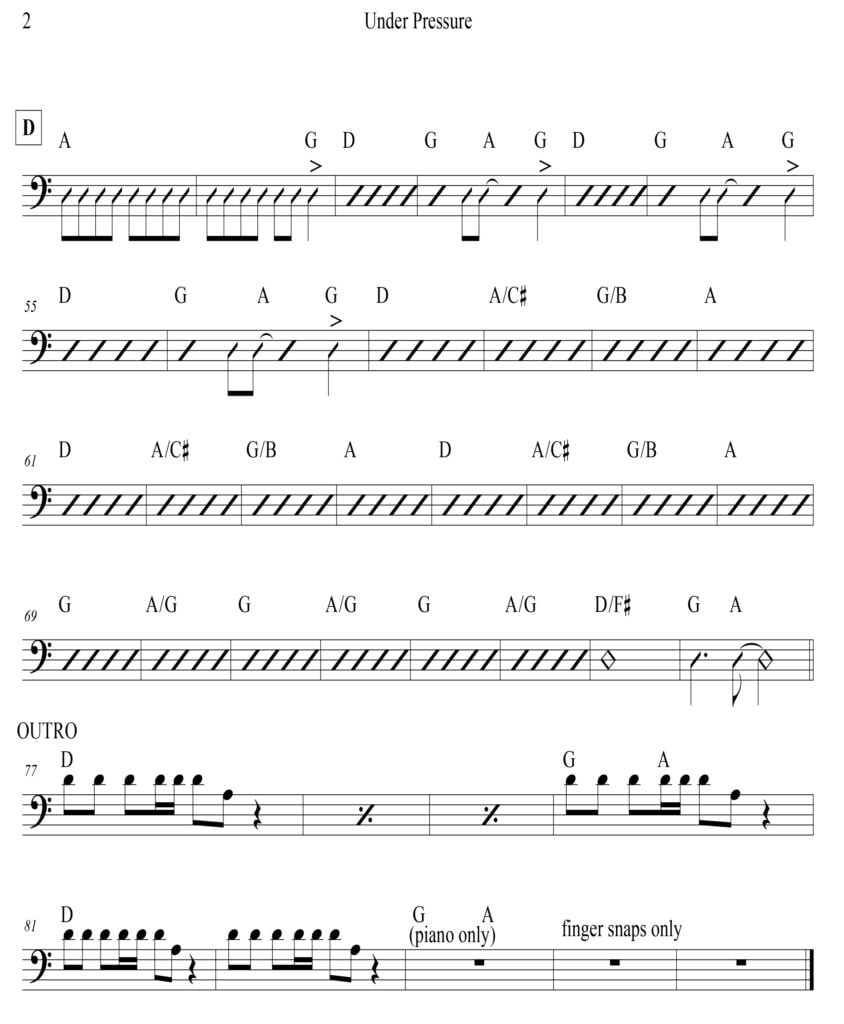

Along with traditional notation, drummers should be able to read and write other types of charts. Every musical situation is different and sometimes one of these other types fits the bill.

This video shows how drum charts help you learn songs faster:

These include the major landmarks of the song (like melody, dynamics, form and accents), and everyone in the band often reads the same one. These charts won’t have the exact drum pattern written out for you, so the trick is to interpret the information and come up with the right groove, fills and other details.

The more you encounter these charts, the better you’ll get at using your ear and intuition to fill in the blanks.

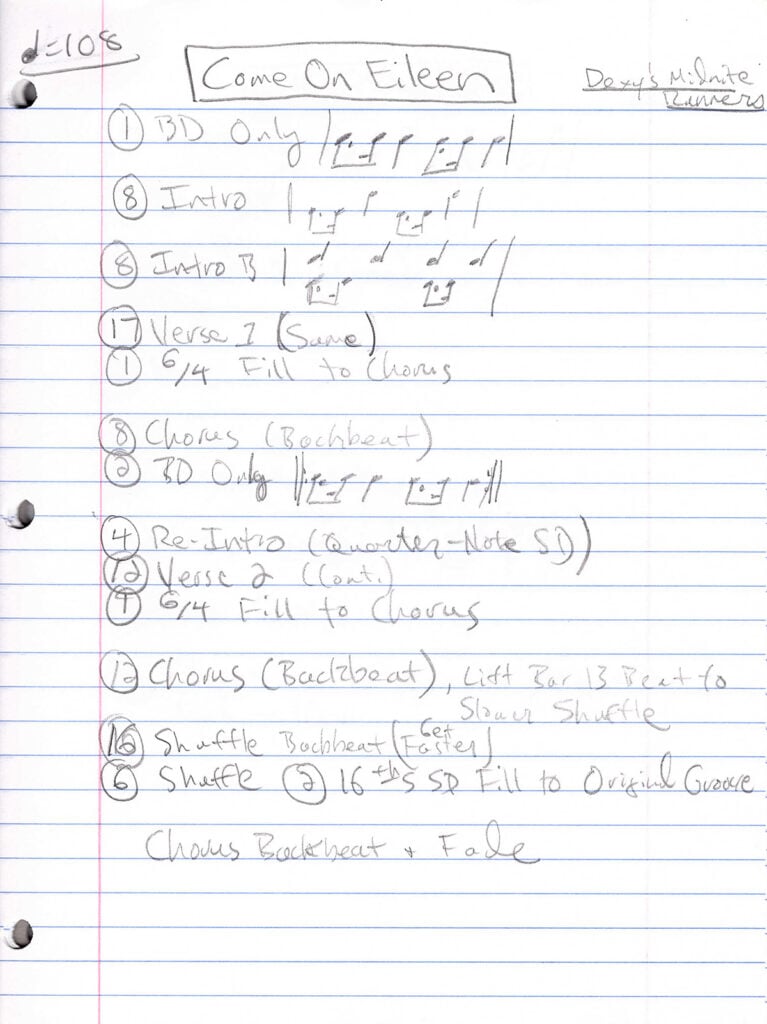

These are “drummer shorthand” charts you can create if you’re learning a song by ear. Road maps give you the information you need to get through the song before you’ve completely memorized it.

They should contain the number of measures in each section, notes on the dynamics, fills and hits, and any other information that could be helpful in playing the tune.

For a detailed run-down on how to create road maps, check out this article.

Drum tabs are another type of shorthand that can help you learn patterns if you don’t know how to read music. This style of notation is more commonly used by guitar players, but it’s good to know how it works.

Each piece of the drum is symbolized in abbreviated fashion on a horizontal line while different letters indicate various ways to strike them. Instead of rests, the spaces between the notes are indicated with dashes.

Here are some of the most common symbols:

x – Cymbal or hi-hat

X – Accented cymbal

o – Normal hit on a drum or open hi-hat

O – An accented note on a drum

g – A quieter note

f – Flam

d – A bounced note or drag

b – Ride cymbal bell

@ – Snare rim

Drum notation has many similarities to the music written for other instruments, but there are also a ton of important differences. Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced player, knowing how to recognize and interpret the notes, rests, dynamics and directions in a drum chart will help you become a better player and a stronger overall musician.

Did you know Drumeo has thousands of beginner drum lessons, video courses, sheet music and practice tools for drummers just like you?

Rob Mitzner is a New York-based session drummer who has recorded for Billboard Top-10 charting albums, films and Broadway shows, performing live at Lincoln Center, The Smithsonian, Caesar’s Palace, The Blue Note, Boston Symphony Hall and for President Obama in his hometown of Washington D.C. He is currently working on a drum book with Hudson Music and has also been featured in Downbeat Magazine and Modern Drummer, and on the national TV show “Trending Today” on Vice. Rob holds a B.A. in Music and Political Science from Brown University, and is a proud endorser of Paiste Cymbals, Remo drum heads, Hendrix Drums, and Drumdots.

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »