Over the last 14 years, I’ve met lots of friendly people around the world who have asked me, “Hey! I just started playing drums and I’m really excited about it! Do you have any advice for someone starting out?”

I often get kind of flustered in search of an answer. Picking up the drums is such an exciting moment in anyone’s life. All of us can relate to that feeling of being completely enamored with the endless possibilities that lie ahead of us in the world of music, and with drumming, specifically.

There’s so much to learn…where do I even begin?

In the moment, I try to ask myself, “What would you have liked to know, back when you were starting to learn?” Even as the son of an accomplished musician and sick drummer, I had so many questions that felt unanswerable when I first picked up drumsticks.

It felt like complete option paralysis. The big, scary music world is out there, full of possibilities, but I had no clue where to start.

I hate to let them down with a generic, short answer, like, “Wellllll…always have fun! And work hard!” for the fear of them looking at me like, “Um, yeah, no fucking shit.” Though that’s a true and heartfelt sentiment, I just wish I had a few hours to share the advice I really want to give them.

–

When I was 14 years old, I had one single aspiration that consumed my thoughts. It was the largest undertaking I could conceive of, at the time — and I believed that if I worked hard enough, I might have a chance at turning this dream into a reality.

More than anything in the world, I wanted to follow in the footsteps of my ice hockey teammate’s older brother, start a hardcore/metal/punk band, and play a show at Chubby’s — a bar in Red Bank, NJ that was across the bridge from Middletown, where I grew up.

One show. That was my fixation.

There were just a few obstacles in my way: I had no idea how to play drums, and very few friends who shared an interest in the music I loved…much less the passion and motivation to learn how to play an instrument, start a band, and practice to be good enough to play at Chubby’s on what seemed like the hugest stage imaginable.

In retrospect, you could probably fit about 30 people in that space. But to me, it might as well have been Wembley Stadium, it was so daunting. Still, it was what kept me up at night, and I made a promise to myself — I’ll do whatever it takes to play a show at this (in my mind) legendary venue.

Zooming out a little bit, it was probably an effort to find my own place in a small, yet vibrant and passionate music scene in central New Jersey — where I totally didn’t fit in as a teenager. The supposed “cool kids” in that Red Bank clique would ditch class to smoke cigarettes outside the 7-11, had killer mosh pit moves and a respectable knowledge of underground local metal and hardcore.

By contrast, I was incredibly lame. I was at hockey practice every day, did well in school, and rarely stayed up past 9 PM. Some of that crowd started awesome bands that played at Chubby’s, or at the internet cafe across the street, or the Middletown Knights of Columbus on Route 36…or if they were REALLY big, The Stone Pony in Asbury Park.

I worshipped those bands. They were from my area, actively engaged in something that I wanted to be a part of so badly, but I had no clue where to start.

I had a lot of exposure to music from an early age. My parents played my sister and me tons of classical music until they deemed us “ready” to learn about rock and roll when I was five. That’s how I fell in love with The Who, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin…all the classics.

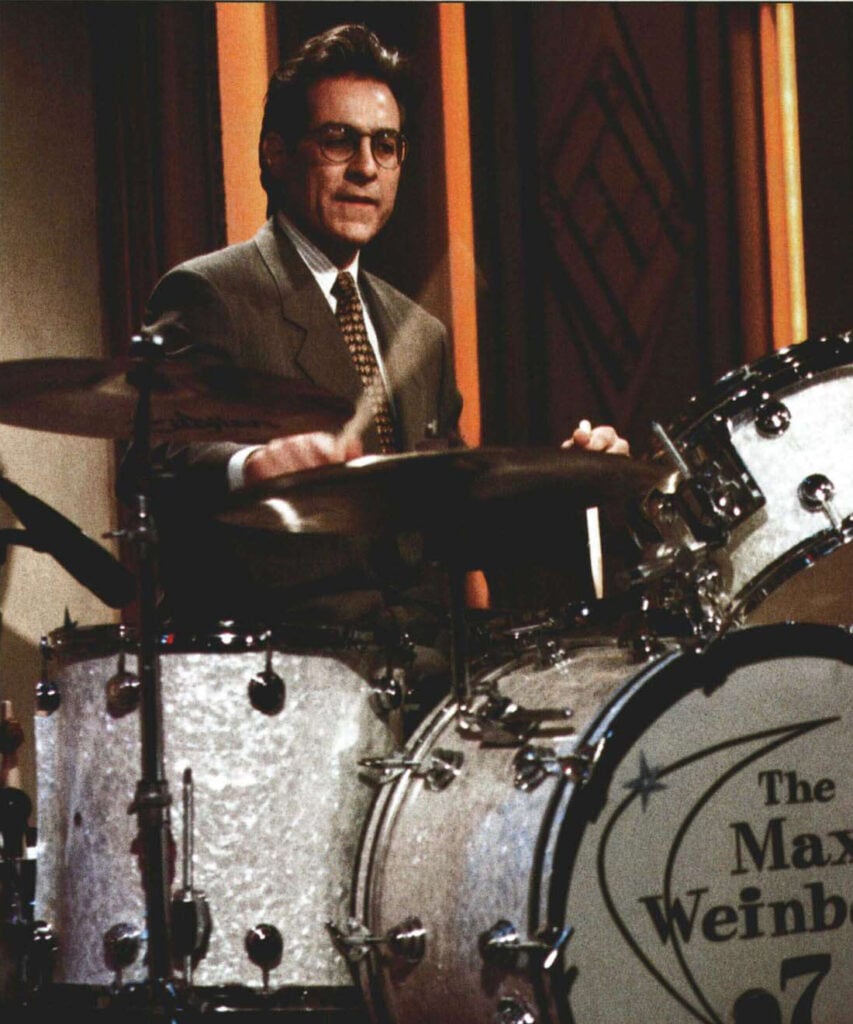

I had no frame of reference for my father’s professional rocking endeavors. I was certainly too young to watch Late Night with Conan O’Brien (the TV program for which my dad was the bandleader from 1993 until 2009), and I only knew Bruce Springsteen as my parents’ friend whose farm we’d visit from time to time.

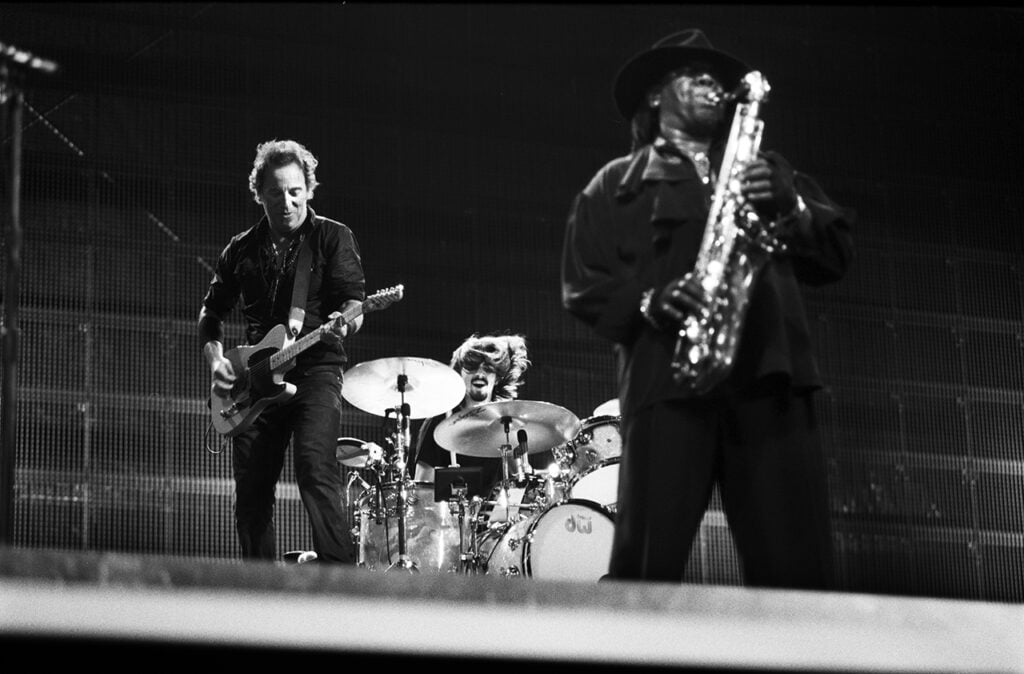

It wasn’t until Bruce and the E Street Band reunited when I was nine that I learned my dad was even in a band, much less one that was popular and culturally significant.

When they resumed touring, I was all of a sudden watching my dad — the same “normal” dude who would drive me to my 6 AM hockey practices and games all around the tri-state area — transform into a superhero, smashing the drums in front of 60,000 screaming fans every night. Luckily, since my mom was a high school history teacher, our grade school allowed her to take our curriculums on tour so she could “road school” us from 1999 until 2004 when I started high school.

We’d head out with the E Street Band for a few months at a time, and she ran our daily routine like a drill sergeant: homework and tests from 7 AM until the afternoon, then hit a museum to absorb the local culture and art. Then we’d make our way to the venue to watch Dad, Bruce, and the E Street Band masterfully deliver a near-four-hour set of relentless rock and roll power to a packed football stadium.

I had no context or preparation for that experience, but I quickly became familiar with the songs they’d play every night, and — looking back, even more importantly — I absorbed their work ethic, and how they conducted themselves as professionals. I admired how hard they applied themselves to their craft; how each of them would come off stage dripping with sweat, having poured their entire hearts and souls into that night’s performance.

Specifically my dad, because until then, I had never seen him become the version of himself that he is when he’s playing those songs on that stage. He would become another person entirely. A driving force — mighty and ferocious, yet controlled — that propelled this music forward, and left city after city in rubble after countless nights of serious rocking.

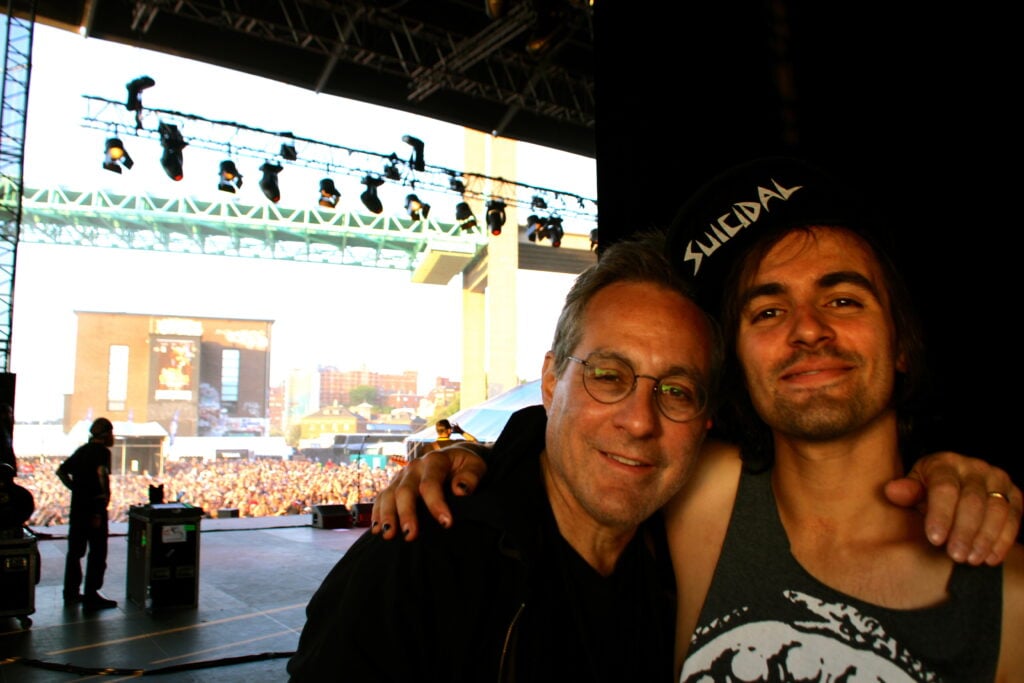

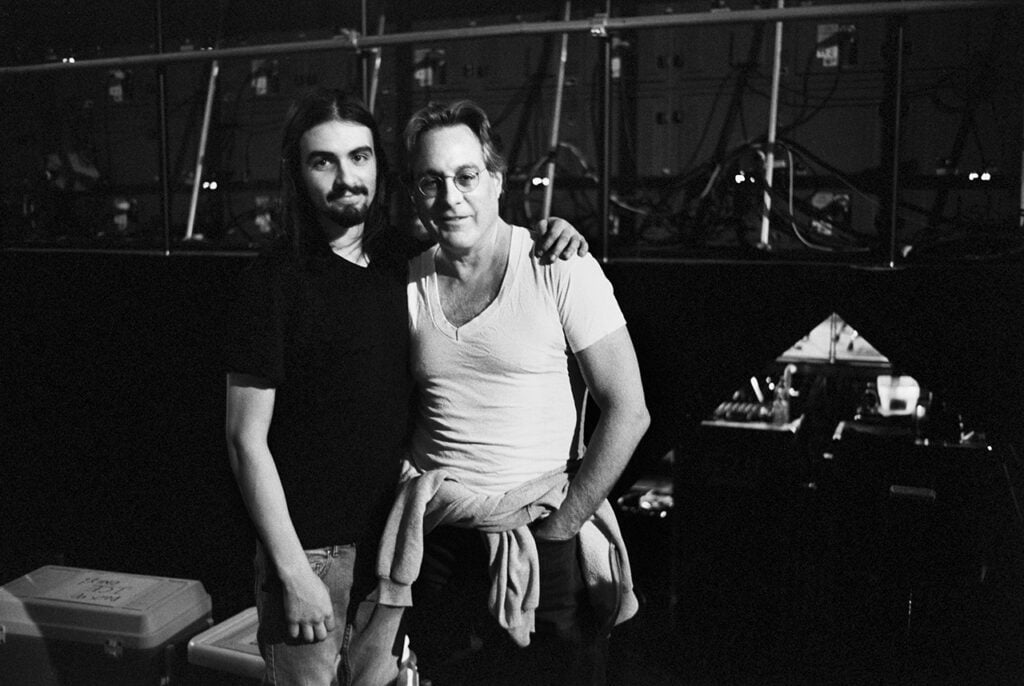

To this day, it’s one of my greatest joys to watch him perform in that capacity, made even greater by the fact that 23 years later as father and son, we relate to each other in the same pursuit and effort. Perhaps different styles, but it all stems from that thing that drives all of us — whatever it is that compels us to endlessly search for the magic within performance, and gives our lives purpose and meaning.

My musical education from 1999 to 2004 was twofold. I was getting a nightly lesson in professional rocking by nature of traveling with the E Street Band, but I was also developing an affinity for music that I could call “my own” — not hand-me-down records from my parents, but sounds that were new and exciting.

Though I’ve held The Who’s Quadrophenia — especially Keith Moon’s over-the-top, innovative style of playing — in high regard over pretty much everything else since I was a youngster, I was craving more. More intensity, more volume, more density, more physicality.

I equate it to the feeling I got being an ice hockey goalie at the time. For whatever twisted reason, I loved the feeling of getting hit in the chest with a slap shot. Still do. The physical sensation of impact and the satisfaction of accomplishing my prime directive — stopping the puck — fed into my budding desire to hit stuff.

–

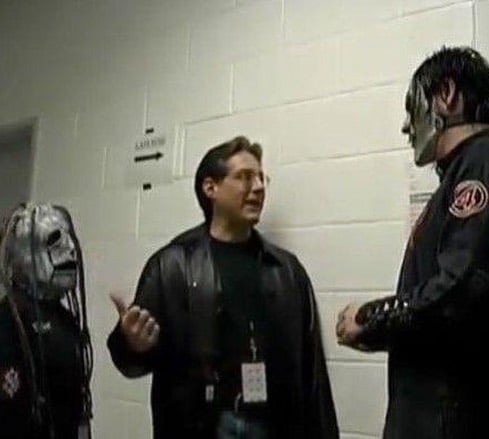

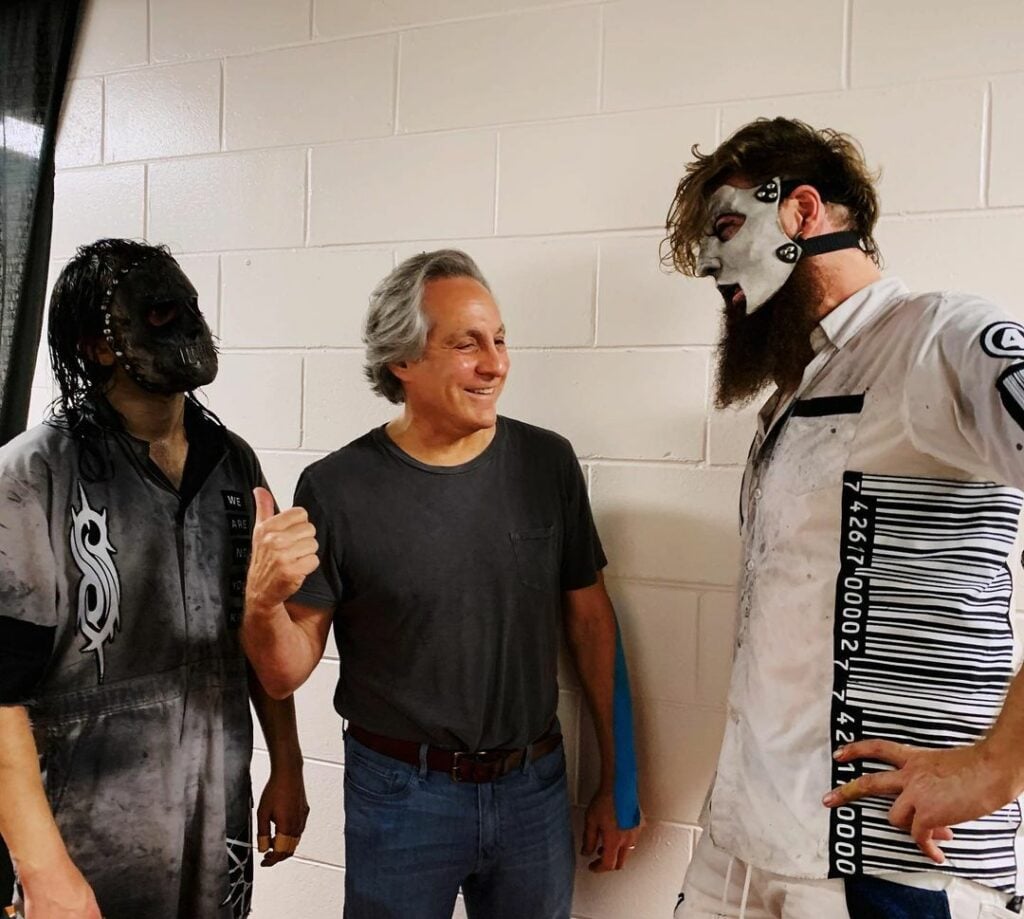

In the early 2000s, it was a chance encounter with the band Slipknot (as they appeared on Conan promoting their debut album) that introduced me to a style of music that allowed me to feel like I had finally found my community and my purpose.

With a gut feeling that I might take to this powerful, energetic, heavy-art-on-steroids style of music, my dad approached them after they had ripped through a performance of “Wait and Bleed.”

“Wow, you guys are pretty insane. My 10-year-old is gonna lose his mind when I show him your record.”

The guys were kind enough to invite our family to their next show in our area: August 11, 2001 as they rolled through on the traveling Ozzfest tour. To his credit, my dad took them up on it, and my life was changed forever.

I’m sure many of you reading this can relate; what I witnessed was unlike anything I had ever seen or heard — completely larger than life and monstrous. We said a quick hello after they played (well, I was likely catatonic and silent from just having my brain pulverized by my new favorite band) and made plans to hopefully see them play again at their next show in the area: October 31, 2001 as they headlined the Pledge of Allegiance tour in support of their new album, Iowa.

I got way into the spirit, dressed up in full Slipknot regalia to trick or treat around town (legit true story), and we made our way to the show. Clown, one of the co-founders of the band, remarks nowadays that he asked me to take off the mask and hang for a bit when we came backstage to say hello, and I refused.

I like to think that’s where our friendship and bond started.

We stayed in touch, and I would come see the guys whenever they came through town — especially when I became old enough to take the train and go to their shows by myself. The experience placed me on a path of self-discovery, and I wanted to learn everything I could about this new music I had found.

As a studious kid, I did my homework and researched as many bands as I could. Thankfully, my parents were supportive of this exploration, and didn’t question the chaotic noise coming from my room. I’d scour the CD aisles at Jack’s Music Shoppe in Red Bank most days after school to find more and more albums that might speak to me in similar ways.

My Slipknot records led me to discover Metallica and Slayer records, and — as most of us do — I embarked on a self-guided history lesson to satisfy this new, voracious appetite for heavy music. Still, I didn’t feel a calling to pick up an instrument myself and take a stab at creating my own sounds. It was all very overwhelming, and I was just enjoying the process of learning — taking in all this brand new artistic stimuli.

It wasn’t until I discovered punk rock at 12 years old, when a teammate’s dad played me Bad Religion’s Recipe For Hate on the way to practice, that I even began to consider playing an instrument. I wanted to at least try to pick up a guitar and play the opening riff to “American Jesus” over and over again.

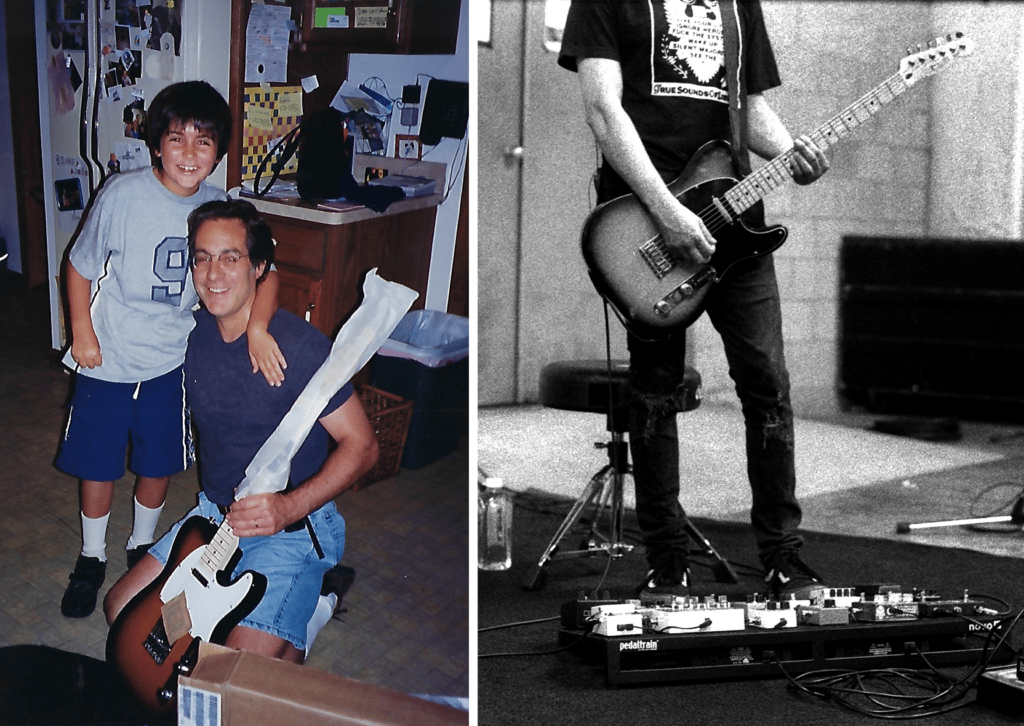

Years prior, my dad had surprised me with a Fender Telecaster (similar to Bruce’s…shocker) for my birthday, but I had always been too intimidated to pick it up and try to play. But now, with a bite-sized, manageable goal — learning the “American Jesus” riff — I felt motivated to give it a shot. I fumbled around with the strings, but eventually got the hang of it.

Thinking about it now, the satisfaction I got from accomplishing that small goal set the template for how I’d approach music for the following 20 years. (Also, fun fact: that exact Telecaster is still really the only guitar I use when I write and record music today).

Punk rock gave me such a gift in that it delivered the intensity, speed, and emotion of heavy metal — but it felt more approachable in that I could apply myself to playing it, and feel my technical progress manifesting to meet my small goals relatively quickly.

Is that a fancy way of saying punk rock is just “easy” music to play? Maybe. But, to me, it was — and still is — a vehicle for conveying the most direct emotion and impact through music. It allowed me to take the complex feelings and changes that every young person who feels like a loner goes through, and to funnel it into making some fucked up noise that seemed within my reach.

There wasn’t a prerequisite to possess a high level of faculty, or to execute a virtuosic performance that seemed out of the realm of possibility. The opportunity to play punk rock music was all right there in front of me. In the same way that those technically-impressive metal records affected me a few years earlier, my Bad Religion records led me to albums by The Ramones, Black Flag, and The Misfits (of course I fell head over heels in love with their imagery and artwork, too).

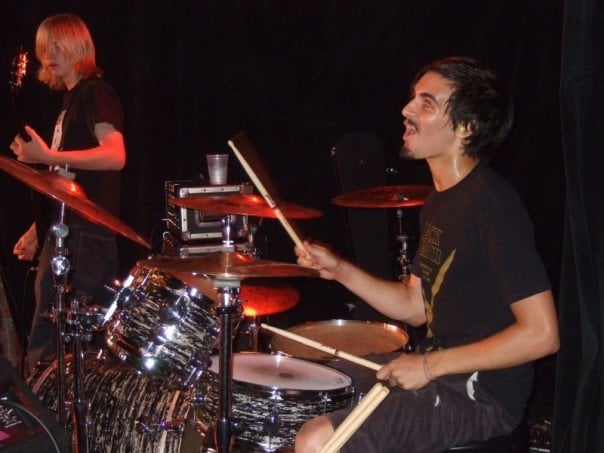

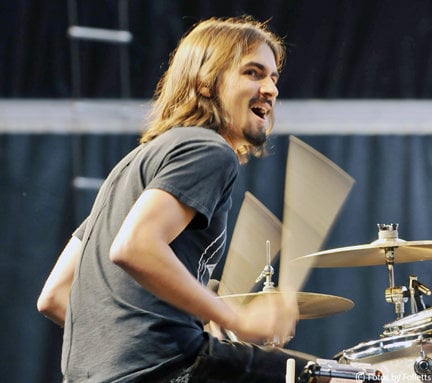

Newer bands that incorporated melody into their sound like The Used became quick favorites of mine. I credit their founding drummer Branden Steineckert with giving me that motivational push to start playing drums. He, too, came from a background of punk rock that seemed so primal and instinctive, and most impressively, he looked like he was enjoying himself.

That made an enormous impact on me. “Wait a second…you don’t have to be all doom and gloom to be a punk rock drummer? You can beat the shit out of the drums and have a good time? Sign me up!”

A short while later, I set up one of my dad’s old drum sets in our basement and started to figure it out.

–

By the time I started high school, I was completely immersed in the world of heavy metal, punk rock, and hardcore. It had become the absolute core of my identity. I was obsessed with local bands that I could see at nearby VFW halls every month: Dahlia, Gaussian Surface, and What About Frank? (later called The Parlor Mob; hometown heroes who would have an influential presence in my life).

I started teaching myself to play drums along to my favorite CDs. I’d come home from school, hole up in the basement for five hours, and try to keep pace playing along with The Ramones’ It’s Alive album (in my opinion, the greatest live record of all time).

Once playing along with Tommy Ramones’ signature rhythms felt like it was coming to me naturally, I wanted to take a stab at something a little more challenging. Enter Master of Puppets. Then Reign in Blood.

I wasn’t keeping a progress chart or anything, but I viewed my ability to play along with my favorite songs and albums as steps on a ladder — incremental goals that seemed to be the next logical steps, once I felt like I could perform alongside an entire album.

I didn’t feel intimidated by the process of learning anymore. What once felt daunting, scary, and far greater than my abilities now seemed to feel increasingly more within my grasp the more I applied myself. And I was doing so in complete isolation, so no one could judge or critique my progress! It was just for the pure joy of immersing myself deeper within the music that meant so much to me.

A few months into my freshman year, I’d developed enough confidence in my abilities to ask the only other metalhead in my high school — an intimidating senior from the wrestling team who I heard played guitar — if he wanted to jam sometime. It would be the first time I’d ever play music with another person; the intuitive next step to starting a band, I figured.

We got together, hacked through some Metallica and Lamb of God songs we both knew, and had a blast doing it. We developed a friendship pretty quickly, and invited his two friends — a vocalist and bassist from his grade — to join in.

All of a sudden, it was happening! I was in a band!

The pure joy and satisfaction I felt when we practiced and started to compose some original material meant everything to me.

I was completely hooked on the process of not only developing my passion for this newfound instrument, but feeling part of something larger than myself. At the time, it felt especially meaningful that I was being accepted into a fold of “cool kids” who were older than me. As a freshman in a band of seniors, I felt a need to rise to the occasion and “play up” — a lesson I’d learned playing hockey years prior.

Starting out as a goalie, I knew if I only practiced with players who shared my novice skill level, I’d probably remain a novice athlete. But if I pushed myself and hopped in net with guys who were four or five years older than me shooting the pucks, I might have a better chance at developing my skills further out of the sheer necessity to keep pace.

I applied that same mentality to playing music with my new, older bandmates. It served me well, because being the youngest member (by far) in the group has been a common theme over the last 20 years. The pressure to rise to the occasion and perform activates some sort of deep, lizard-brain instinct to survive. It’s always driven me to bring my absolute best to the table.

After a few months of practicing and writing, we had come up with enough material to justify trying to book our first show. I had seen the logo for a local promoter on the flyers for tons of hardcore and metal shows at venues around town.

I looked up their phone number, cold-called them, and asked what we’d need to do to jump on one of their shows. They told me that if we could sell 20 tickets, we could have the opening slot of a local show coming up at The Saint — a classic dive bar/musical institution in Asbury Park.

“Deal!”

I had just booked my first band’s first show, and all we had to do was sell 20 tickets to our friends and family. It wasn’t Chubby’s, but The Saint was on that same general Central Jersey music circuit. We were in!

I was elated that, in the seven months between September and April, I had put one foot in front of the other enough times that I had taught myself to play a new instrument, focused my attention on trying to play the style of music I loved, met three similarly-minded people, started a band, and booked our first live performance. I was stoked.

Admittedly…we kind of sucked. But we didn’t care. We continued to practice, hang out and talk about our love for our favorite bands, go to shows, and do all the things that teenagers do in their first high school band. My connection to playing this music was instant; I was obsessed, I had found my calling, and I made the decision that I would devote myself to a life of music — whatever that meant.

I called my high school hockey coach, told him that I didn’t want to “half-ass” being a hockey player and a drummer at the same time, and that I wouldn’t be returning to the team that summer. I wanted to chase my new dream of being a musician.

That first band eventually dissolved, but I was already set on an absolute warpath to play drums all the time. I needed to start another band into which I’d funnel my time, attention, and energy.

There was a fantastic local drum shop in Red Bank called Drummer’s Alley, where I’d wander in sometimes after school to buy new sticks, and marvel at posters of my idols: Lars Ulrich, Dave Lombardo, and the like. There was a bulletin board where people often posted “Drummer Wanted” ads, and as fate would have it, I saw a Post-It note with some chicken-scratched, half-legible handwriting:

“Drummer Wanted for Metal Band. We like Metallica, Slayer, Sabbath, and Maiden.”

Boom, I found my new dudes. Turns out we were all the same age, and one of them was a kid with whom I went to grade school! Perfect.

We got right to work playing covers we loved (ranging from the Melvins to the Sisters of Mercy) and writing our own tunes. I came to appreciate the work ethic and application of my new bandmates. They shared the same hunger that I did.

Every chance I got during my high school “free periods,” I was emailing local promoters to book shows, and we’d get opportunities to open up local gigs at The Saint, the Route 36 Knights of Columbus, recreation centers, the internet cafe, and yes…

Chubby’s!

I had finally realized that dream of mine, but I didn’t feel satisfied. Not even close. To me, it just meant that I had to find the logical, next incremental step on the path of pushing myself forward, musically. Besides practicing with my bandmates every day, I’d continue spending my free periods at school booking shows and reaching out to other local bands to try and play together.

I opted to take my school’s Graphics & Design elective course so I would have access to a computer with Photoshop, where I could design flyers for these events — my first foray into art and design. If there was a free moment of my day that I could devote to the band, that’s what I did.

I had finally realized that dream of mine, but I didn’t feel satisfied. Not even close.

We were together for our remaining three years of high school, checking off some more reasonably-attainable goals that I had dreamed of accomplishing.

Book a show outside of New Jersey: check.

Record an EP: check.

Book a tour (well, three shows in three days between Jersey and Philly): check.

As high school was ending, the writing was kind of on the wall for the band. Three of us were going to different colleges, and our guitarist was going to enlist in the Army. So I worked my ass off for the few months before summer to book us our most ambitious jaunt yet: a week and a half of shows from New Jersey to Florida and back.

Our other guitarist’s dad owned a Dodge dealership in town, so he let us quietly take one of the used vans off the lot if we promised to bring it back in one piece. It was so cool; we were all 17, driving around in a van, playing shows in dives and cafes to basically no one…totally living the dream.

Nevertheless, it was bittersweet. I knew that once we got home, it would be impossible to continue the band with the same ferocity. Digital collaboration and working on music by proxy wasn’t as easy as it is with the technology we have today. If we couldn’t jam after school every day, it just made sense to break up.

So we did. It was a bummer.

While I was running around with my high school band during the summer of 2008, my dad was out on the road with Bruce and the E Street Band supporting their album Magic. I came home from our short “tour” pretty depressed that our band was ending, and that I’d be turning my attention to being a full-time college student pretty soon.

Don’t get me wrong, I was appreciative of the opportunity to go to school and pursue my education, but I was puzzled as to how I’d find time to devote myself to music without shortchanging the experience. “Half-assing” it was not an option to me.

I tried to maintain some optimism and spent the rest of the summer doing something I loved: watching the E Street Band destroy nightly, and marveling at their musical prowess and intensity.

When the band got back together in 1999, it became a sort of tradition for any of the band members’ kids who had taken up an instrument to jump on stage and sit in for a song or two. It was pretty mind-blowing to see my sister Ali, a talented pianist at the age of 12, sit in on Danny Federici’s organ for “Ramrod” and “Dancing in the Dark” at Madison Square Garden.

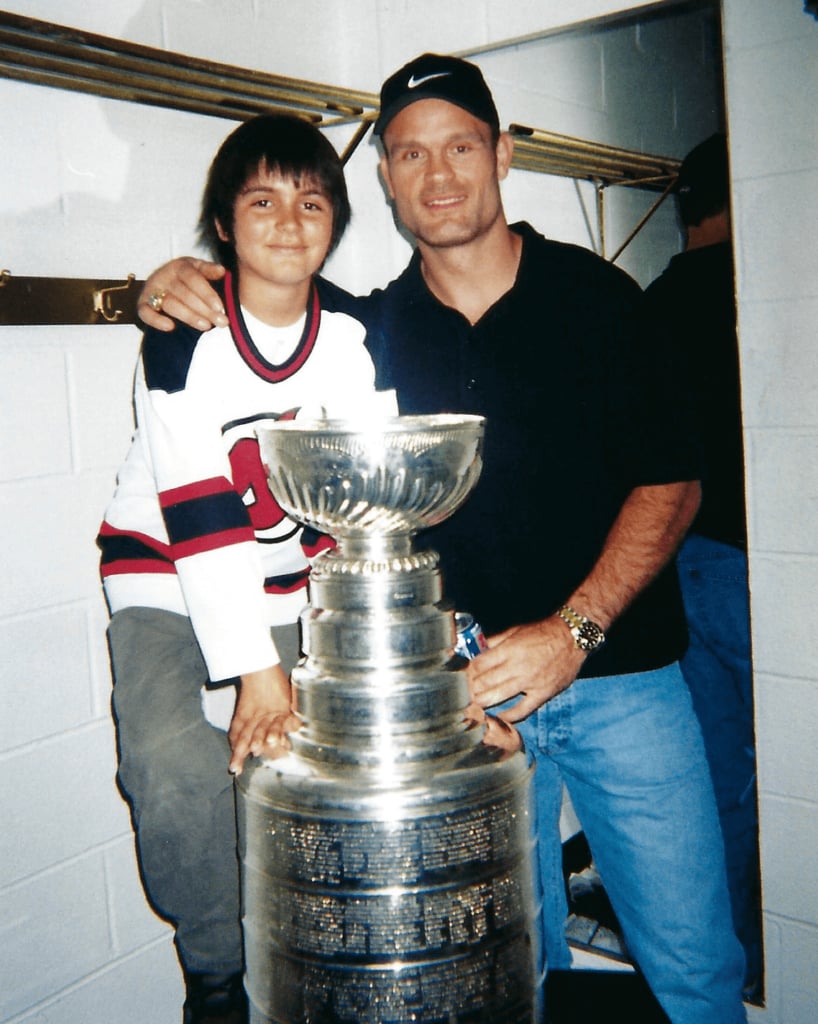

I was nine, and couldn’t even conceive of that pressure to perform, in front of thousands of people, at the legendary arena where our family would often go see our beloved New Jersey Devils play. Hell, I’m 32 now, and that still seems nerve-wracking. But I’d see several of my friends in the E Street kids’ group get up with the band over the years; on guitar, saxophone, accordion, harmonica…and I was continually impressed watching them do it.

After nine years of us traveling with the band, I was the last remaining offspring who still hadn’t gotten up on stage with them. To me, the thought of playing in front of that many people was absolutely terrifying.

Knowing I was down in the dumps about my band calling it quits, my dad asked if I’d like to sit in with them at one of their soundchecks. Maybe that would lift my spirits, to play a song with my uncles and aunts in the E Street Band. No fans in the building, no real pressure…just for fun. To realize that my musical endeavors aren’t over; that I’ll still find ways to play.

I took him up on the challenge, and made it my goal to learn how to play one of my favorite songs, “Born to Run.” It’s an iconic anthem that sends a wave of electricity throughout the entire stadium when they play it.

The song has always had a profound effect on me. I thought that would be a meaningful one to take a shot at. After all, what’s the worst that could happen? Bruce and the band were like family to me, so that made the idea of playing a song with them in an empty building less intimidating, in a way.

We’ll just have fun playing this one song. Another manageable goal that I was able to set for myself.

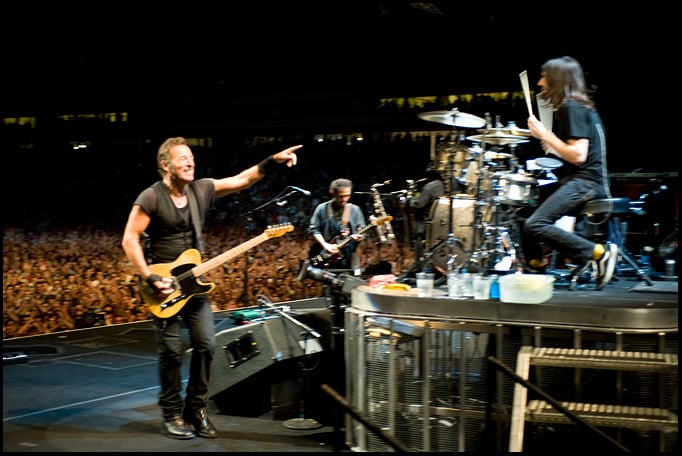

On July 28, 2008 at Giants Stadium, after Bruce and the band had rehearsed some deep cuts that they were planning to bust out that night, I hopped up on my dad’s drum riser and asked if I could play a song with them.

“Which one?” Bruce asked.

“Can we do ‘Born to Run’?” I looked around me to see the looks on all my dad’s bandmates’ faces; a mix of confusion, intrigue, and excitement.

None of them had seen me play drums until this moment. They looked at my dad, and he shrugged, as if to say “Welp, let’s see what happens!”

Bruce counted the song off in his trademark “ONE, TWO!” I played the beginning half-measure 16th-note snare roll, and we were off to the races. The experience was unlike anything I’d ever done before. It was about as exhilarating as I imagine playing “Born to Run” on a car stereo would be…if that car was a Ferrari and I had just floored it out of the cargo hold of an airplane flying at 40,000 feet.

Pure adrenaline and delight.

We came to the end of the song, and I was thrilled that I had gotten through the whole thing without sending it off the rails. Seeing Bruce and the band smiling and laughing, it seemed like they had a good time letting me live out a little bit of a dream with them. Shaking with nerves, elation, and satisfaction that I had taken my dad up on his challenge to me, we high-fived, hugged, and I left the stage to reflect on what had just happened.

I thought to myself, “I…just…technically played ‘Born to Run’ at Giants Stadium…SICK!” My dad was right. That was the musical pick-me-up that I needed. I was truly thankful for the opportunity, and what it did to boost my mood.

I did not, however, expect what would happen next.

Bruce found me at the foot of the ramp to the stage after soundcheck and said, “Hey, that felt pretty good…want to play it tonight?”

My stomach turned into knots. My hands and feet went numb. Until then, besides sitting in with a few friends’ bands now and again, I hadn’t played in front of more than 50 people with my high school bands. Regardless of the fact that they were like family to me, it was intimidating enough playing on stage with these professional rock legends in an empty room.

But I’d just been asked by the man himself to sit in with them — Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band — on “Born to Run”, arguably their most recognizable song, five weeks before my 18th birthday, in front of a sold-out Giants Stadium crowd.

I mean, he’s THE Boss. What am I gonna say?

Not knowing quite how to respond, but absolutely refusing to decline his offer, I nervously said, “Uhhhh…yeah!” It was on.

Yikes.

Up until this point in my musical endeavors, I had systematically and methodically placed these reachable goals in front of myself to work hard, push myself out of my comfort zone, accomplish those goals, and move on to the next challenge that I could reasonably pull off. I’d be a fool to not acknowledge that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity — a gift from my father and Uncle Bruce — along this creative path; to find out what it’s like to perform an iconic rock anthem in front of an enormous crowd.

I’d be a fool to not acknowledge that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

I’d likely never do anything like it again in my life. And I was completely happy with that! I could ride off into the sunset, satisfied that I’d risen to the occasion to play a song with my family in front of a ton of people.

A ball of coiled nerves on the side of the stage, I had to watch them play 24 songs before “Born to Run” was next on the setlist. Two-and-a-half hours felt like an eternity.

They hit the last note of that 24th song, “Detroit Medley” — a single song comprised of Shorty Long’s “Devil with a Blue Dress On” and Little Richard’s “Good Golly Miss Molly,” as covered by Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels. And as they sustained the last note, I walked up onto my dad’s drum riser, just as I had earlier that day at soundcheck.

I looked out at 70,000 diehard New Jersey-based Bruce fans…the realest of the real…and caught Bruce smiling at me. I couldn’t believe what I was looking at.

Bruce turned to the crowd — likely confused as to why Max had left the stage, and wondering about this kid who had jumped on his kit — and explained, “That’s Max’s kid, Jay Weinberg on the drums!”

He counted the song off, just as he had done earlier, and we launched into it. The performance was a complete out-of-body experience. It was a moment that I knew I, my dad, and the rest of our family would remember for the rest of our lives.

I honestly sort of blacked out for the entire thing, it was so overwhelming. Thank goodness it went well.

Play a show at Chubby’s: check.

Play a song at Giants Stadium? Whoa. Check.

I ultimately decided to attend Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ. A fantastic school in its own right, but more importantly to me, it was a 10-minute subway ride to New York City. I knew that with my proximity to a city that’s bursting at the seams with creativity, I’d increase my chances of finding new bandmates with whom to play.

Luckily, MySpace had already come into prominence, so I went to the “New York City Musicians Wanted” message board and answered every single ad looking for a drummer. I’d show up, audition, and play shows with a bunch of them. Some were quite good, and I had a lot of fun jamming, practicing, playing shows, and just overall honing my chops with all sorts of musicians.

I was enjoying being a college student and playing locally all over Manhattan and Brooklyn. Playing all the time was of the utmost importance to me, and that became my new realistic, attainable goal: play with as many people as possible, in as many styles as possible, and just keep developing as a musician.

During my December break from college, I went back home and learned that my dad would be moving to California, as the Late Night TV show in New York was moving to Burbank for Conan to become the new host of the Tonight Show. As their schedule began to present itself, we learned that the new Tonight Show was slated to debut on June 1, 2009.

Coincidentally, Bruce and the band had a European Tour slated to begin on May 30, 2009, presenting a clear scheduling conflict. My dad would have to be in two places at once.

“Damn, that sucks. What are you going to do?” I asked him. He didn’t really have an answer.

A few days later, as my dad was driving me back to Hoboken, my phone rang. It was Bruce.

Caught off guard, I picked up, not really sure how to answer. We chatted for a minute, and then he got right to his reason for calling. I’ll never forget how he began:

“Well, Jay, as you know, I have the world’s greatest band. And in this band, we happen to have the world’s greatest drummer. Now, this great drummer has a scheduling conflict that’s going to keep him from playing with us for a little while, and we need to find someone to fill in for him. When I asked him for any recommendations, he gave me your name and number.”

Stunned, I looked at my dad. Not taking his eyes off the road, he had this sly grin on his face. I stammered to find some sort of response.

“Are you serious?” I asked Bruce.

“Dead serious,” he answered.

Of the many twists and turns I had come to learn about their storied career, this was yet another classic Bruce, classic E Street Band way to overcome an obstacle — all while keeping it in the family.

Just like when he had asked me to play one song during a show five months earlier, what was I going to say?

“No”?

“I’ll have too much math homework at school”?

“Sorry, Mr. Springsteen, but my teacher won’t let me”?

Absolutely not. I knew this had the potential to be a life-changing opportunity, and I needed to approach it with full confidence that I could pull it off — even if it meant I’d have to learn as I went.

While we were on the phone, he told me something that’s stuck with me ever since. He said, “It only takes one song to know what someone’s about. I have a good feeling I know what you’re about.”

After 14 years, I’ve come to understand how true that really is. No matter the musical situation you find yourself in, you can tell when you have undeniable, magical musical chemistry with someone — or a group of people — after playing just one song. No one but my dad had sat on that throne for 35 years, but Bruce basically said, “Well, you know one tune…what’s a few hundred more?”

“It only takes one song to know what someone’s about. I have a good feeling I know what you’re about.”

Bruce and my dad — I believe from the viewpoint of fathers first, not from that of the veritable rock legends that they are — had schemed up a plan for me to fill in while my dad fulfilled his responsibilities to the beginning of the Tonight Show.

Knowing I had only been playing drums for four years, they had to answer tough questions for themselves. “Will this be too much for Jay to handle? Will he crack under the pressure? Is this even fair for us to ask of him? Will we be setting him up for the ultimate embarrassment?”

To be honest, no one knew. To the knowledge of everyone involved, there was no precedent for the son of a well-known rock drummer taking his father’s place while his father was still alive and able to perform — much less for a kid who, while passionate and committed, had only been playing the instrument for a few years.

Their ultimate conclusion was, “Huh. I guess we’ll ask and find out!” They took a real shot in the dark on me, and I’m forever grateful.

The two of them essentially conveyed to me, “You’re going to have to work your ass off. No one is going to cut you any slack. Not us. Not the rest of the band. Ab-so-lutely not the fans. But, if you commit yourself, show us you’re up to the task, and rock an entire show like you did that one song…the opportunity is yours.”

Overwhelmed, but humbled and grateful, I accepted.

Though I was still proud of what I had accomplished throughout my early-to-mid-teens, if I were to pull this off it would, by comparison, be a quantum leap in effort, scale, and scope.

I would immediately commit to a rock and roll crash course unlike any other opportunity imaginable. I knew that the difference between success and failure was dependent strictly on my work ethic, and how hard I would apply myself to what was asked of me. I gave them my word that I’d give it everything I had.

I knew that the difference between success and failure was dependent strictly on my work ethic.

As daunting as it was to be at the precipice of such an insane opportunity — and believe me, I was scared to death — I’m confident that the only reason I felt up to the challenge was from my four years of setting small, manageable, realistic musical goals for myself. Though this would be quite a larger challenge than anything I had faced up to that point, I distilled it into much simpler terms for myself: just a new and exciting challenge.

To prove it to Bruce, to my dad and to the band, to the fans, and most importantly to myself — I was going to do whatever it took to demonstrate I was capable of successfully and faithfully executing the duties that had been requested of me. That set the tone for what became my entire life throughout 2009.

I met with Bruce when they played at that year’s Super Bowl halftime show, and he handed me a list of several hundred songs, saying, “This is what we’ll start out with. Songs we’re definitely going to play. We’ll add to it here and there, but if you can manage this list, you’ll be good.”

I seriously had my work cut out for me, but I was so thrilled. Most of these songs felt like part of my DNA, anyway. For 10 years, I had been watching these guys rip through “Murder, Inc.,” “The Rising,” “Out in the Street” and hundreds of others countless times. Now, I was tasked with studying them to a deeper extent; dialing in the minutiae of the performance, the tempos, the vibe…even just remembering the sheer volume of songs.

Sure, they’re not all 20-minute prog odysseys, but it’s a challenge to remember hundreds of…well…anything, I suppose. And then to have the ability and mental quickness to recall any one of these songs on demand when Bruce invariably switches up the setlist mid-show…I knew I had to be ready for the entire E Street experience.

It’s one aspect of my dad’s playing I’ve always respected so much: his mental agility and his adeptness at seemingly reading Bruce’s mind, anticipating his every move. Countless times, I had seen the band finish a song and sustain the last chord while Bruce shouts out, “Let’s play [insert song no one on stage has played in 30 years]!”

And then everyone just goes for it. It’s understated, but incredibly impressive. I knew something to that degree was expected of me, and I’d have to deliver.

My dad’s playing style is incredibly particular. I’m not the first to say that. There’s only one “Mighty Max.” He’s completely unique in his stature and power, his performance a firm, reliable backbone that’s unwavering in stamina and precision — yet there’s a beautiful finesse to how he maneuvers around his three-piece kit when he wants to show you just how goddamn good he is at the drums.

Me, at eighteen years old? Not as refined…definitely not as experienced…but a pipe bomb of enthusiasm with a lot to prove. My dad knew I respected him and his playing, but now that I was going to be taking his place — even temporarily — he needed to know beyond a shadow of a doubt that I could do the job.

After all, however well or poorly I performed would reflect on him too.

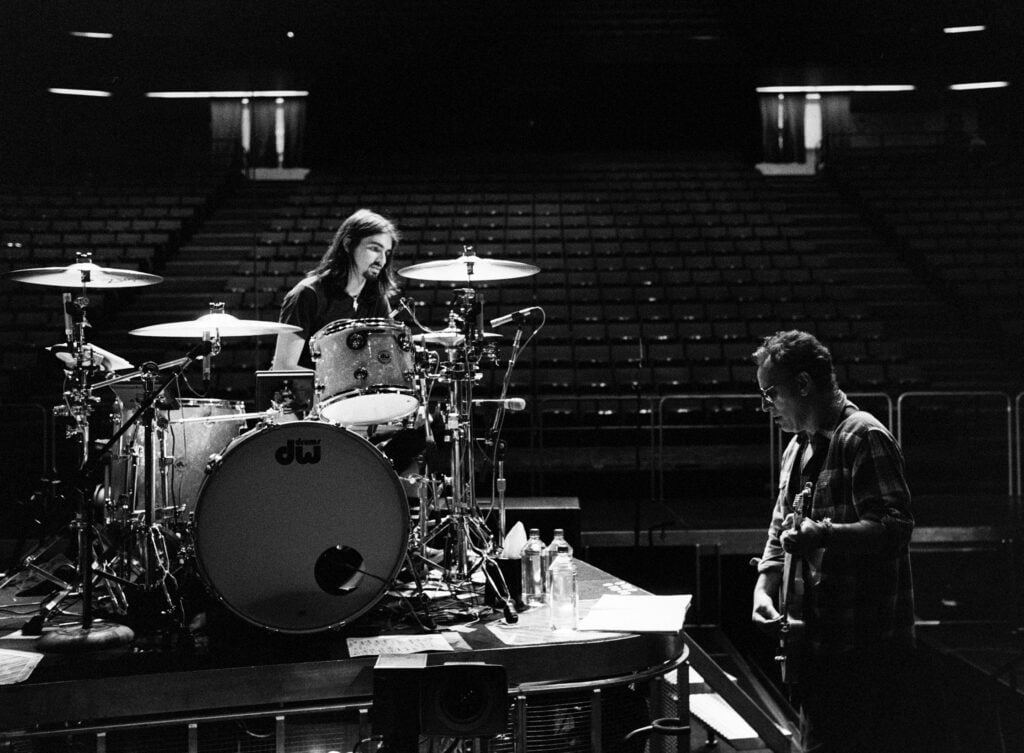

I vividly remember him sitting me down at my drum set with an iPod and headphones, asking me to pick any song on Bruce’s list to play in front of him (to judge, critique, analyze…the works). I think I picked “Badlands.” I got through two bars and he paused the iPod.

“That’s not the bass drum pattern I play. Start over.”

I got through the intro to the first verse, and he paused it again.

“Wrong fill going into the first verse. Start over.”

Straight up like a scene out of Whiplash, I was feeling dejected about my progress already, and this was the first of *checks notes* HOW MANY SONGS?

“Fuck this,” I thought to myself, “If the expectation is for me to play hundreds of songs note-for-note exactly how you play it, I’m doomed.”

I had to draw a line in the sand. I told him, “For the sake of my survival, I just need to focus on the broad strokes here, not the extra-fine details. I’m not you. I’m not going to play this song, or any other song for that matter, exactly the way you play it. Besides knowing the structures, I need to focus on identifying the tones, emotions, and energies of each of these songs — and how that moves me to play them the way I’m going to play them.”

He often equates that experience to the stereotypical parental experience of teaching a child how to drive a car for the first time. “Fuck you, Dad, don’t tell me what to do!”

He understood where I was coming from, and left me to my own devices to figure it out for myself. After all, I had taught myself everything I knew up to that point, and it had turned out alright…

Luckily, I was eased into the tour and didn’t have to play a full three-plus-hour set off the bat. That would have been sadistic, even by stadium-rock band standards. I’d come up for a single song during the encore one night. The next night, I’d play a few songs during the encore. Then I’d play the whole encore…then the last few songs of the main set and the encore. So on and so forth.

Bruce continued to set manageable goals for me to meet within the context of these marathon performances, until we were approaching mid-May and my dad needed to be in Burbank for Tonight Show preparation.

On May 14th, 2009, I was officially left on my own to play my first full Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band show in Albany, NY.

Game on.

I went on to play with them that June in Europe where the crowds were even larger, the onstage energy even more chaotic, and I was in the middle of a controlled musical frenzy every night. Bruce would call out songs of his I had maybe heard a few times, but never actually sat down to practice or play. It didn’t matter; I had to rise to the occasion and just do it.

He’d call out cover songs from their generation I’d never heard of before. “‘Dark End of the Street?’ What is that? Is that a rock song? A ballad? A punk song? A soul tune?” No clue, but Bruce is holding up a fan-made sign that asked us to play it, so here we go.

Whatever…fake it till you make it, baby!

He never coached me with words but, like a conductor, he’d guide me with his onstage mannerisms and movements to show me, as we were playing in front of literally tens of thousands of people, how and what he wanted me to play. I had to trust him, the band, and most importantly myself that we could get through taking musical chances like that.

And, suddenly, four minutes would pass and I just improvised a song I’d never heard of in front of thousands of people. Talk about an adrenaline rush.

There was, however, one moment on the tour that sticks out to me. To this day, any time I find myself thinking about it, I shudder in embarrassment.

We were playing three sold-out nights at Stockholm Stadion in Sweden. The first show had gone incredibly well, as we mostly played songs that were finely-tuned and tight at that point in the tour.

But knowing Bruce’s propensity to shake the setlists up for a multiple-night stand in one city, I knew I had to be on my toes for some wild audibles over the next two shows. You see, some nights Bruce would just write “???” on the setlist instead of three or four song titles. That meant we were just going to make that part of the show up as we went, often pulling more signs for requests from the audience.

On the second night in Stockholm, we were about an hour into the show, sustaining a big open chord as I’m washing on my crash cymbals, watching Bruce go down to the crowd.

He pulled up a sign from the audience that caught his eye.

I saw it, and my heart dropped.

It was a request for “The E Street Shuffle,” a rarely-performed track from his second album that wasn’t on the list of songs I’d been tasked with learning.

At that point on the tour, I had played several handfuls of songs that I didn’t know how to play, or had never played before. That wasn’t a big deal; I was comfortable enough improvising songs with which I was familiar, or that Bruce knew I didn’t know, but he had faith that I could just jam on them and we’d be fine.

I knew this song was different.

It’s a carefully-choreographed, lengthy arrangement with lots of specific accents and a drum solo — not a song that can be improvised.

Bruce held the sign up to the band (who all nodded to him in the affirmative, like “Got it, let’s do it!”). He turned it to a camera, which showed the entire stadium the song that’d just been requested. Thirty-thousand wild Swedes broke out into a deafening roar of enthusiasm.

He turned to catch my eye with a look that seemed to ask, “Wait…do you know this one?”

I looked right into The Boss’s eyes with more disappointment than I’d ever felt in my life, and regretfully shook my head.

“Nope.”

I knew I couldn’t fake the funk on that one, and it would have been a certain train wreck if we’d even attempted it. A stadium of elated cheers suddenly turned into a chorus of boos as we course-corrected to play a different song — not the one they just got so excited to hear.

Bruce laughed, totally understood, picked up a sign for a different song from the pile he had made on stage, and showed us a sign for one we had played on that tour. “Prove It All Night” or something, I’m not sure.

In that moment, I felt infinitesimally small. We launched into the next song, but my brain was on autopilot; stuck in Neutral because of the scene I felt I had just caused. Even though I had successfully learned, played, and rocked so many songs and shows up to that point, I felt like the biggest loser on Earth…and I still had two and a half hours of the concert to endure.

Not only endure, but perform — and perform convincingly.

Mentally, I was shaken. I felt I had let Bruce and the band down, I had let the fans down, and I had let myself down. I tried justifying the event to let myself off the hook.

“Well, the song wasn’t on the list that he had me study! That’s not my fault!”

But I couldn’t convince myself that it wasn’t my fault. It might not have affected anyone else to that extent; maybe a more seasoned professional would have brushed off the moment as not that big of a deal.

In my mind, it was my responsibility to deliver on what the show demanded of me, and in that moment, I had failed.

I remember coming back to our hotel after the show that night, and a group of fans waiting outside booed as I got out of the van and walked inside. I felt awful.

“Maybe the people who doubt me — the people who tell me, ‘I wish it was your dad playing on this tour instead of you’ — are right,” I thought, alone in my room that night. “Maybe I just suck.”

But to my surprise, the sun came up the next morning.

I tried my best to move on, harkening back to my days as a goalie. If I let in a goal, I used to ask myself, “What are you going to do, cry about it? Smack your stick on the net and show the opposing team that you’re rattled? And then probably let in another goal as a result?”

Nope. I had a job to do, and that was to put this unfortunate incident behind me, continue on with this tour, and put on the best performances I possibly could. Not just that, but to shove anyone’s expectations of me up their ass.

Why should I care what they think? As long as Bruce and the band around me are satisfied with my effort and dedication, isn’t that the only thing that matters?

I realized at that moment: it’s just rock and roll.

It’s a living, breathing display of the imperfections we dare to put on display by laying our entire souls on the line, immersing ourselves within song. Sure, so you fucked up…who doesn’t? More importantly, who cares? No one. No one important, at least.

Out of the many lessons I learned during the year I spent on tour with Bruce and the E Street Band, the most important was that even when the pressure is on and the stakes are at their highest, it’s okay to be human.

I took that lesson and even applied it to my neuroses about performing well — up to the E Street standard, specifically. If I messed up on stage and missed a beat, who gives a damn? None of this is meant to be surgically, metronomically, perfectly executed. That’s not what interests me about music, or what drew me to music in the first place.

What interests me is art made by real humans that showcases their human qualities. So much of music is about our relationship with the people we’re playing with, and the energy of the moment. It’s not about worrying that you played one too many kick drum notes going into the chorus. Sometimes human chemistry combusts, causes explosions, and things go awry, but that’s fine.

Music — especially aggressive and loud music — isn’t designed to be held with rubber gloves. Everything can come off the rails at any time, which is a beautiful thing that often gets lost in modern rock and metal. I’d rather watch something completely chaotic, unhinged, and emotional than something that’s sterile, frigid, and lame.

When we discussed my approach to learning those couple hundred songs, Bruce taught me that it’s okay not to learn “parts.” I mean…you should make a concerted effort to play well, and to understand where those songs came from, and why they were arranged that way…but we’re not on stage playing parts. We’re on stage playing music.

It’s a mindset that would continue to serve me in everything I’ve done since.

We’re not on stage playing parts. We’re on stage playing music.

Eventually, my involvement with the tour came to its natural conclusion in the fall of 2009. My dad returned to the band, I went back to being a full-time student, and I’d try to go see them play on the remaining dates whenever I could.

Over the next several years, I’d play with a few hardcore and punk bands, touring quite extensively to the point where I had to leave school in 2011 because my music schedule became too rigorous for me to balance with my studies. I made a promise to myself (and to my mom, the educator in our family) that I’d return at some point, and I ultimately decided to do so at the end of 2012.

All of those touring experiences and opportunities came to an exciting climax in mid-2013 when I received a phone call from an acquaintance who worked at Roadrunner Records. I had met him years prior when he had signed my friends The Parlor Mob. He told me that he had signed a band from Norway who were on their first headlining tour in America, and that their drummer had unfortunately hurt his arm and couldn’t continue playing.

“They’re a band called Kvelertak,” he said, “and they need someone to fill in. I know it’s a lot to ask, but can you learn their set and fly to Seattle tomorrow?”

I didn’t know any of their songs, but I had actually seen them play once before. They were a killer live band and I knew their general vibe: one part Thin Lizzy-esque party metal riffs, one part black metal. I could probably figure it out.

I assured my friend, “Don’t worry about a thing, I’ll learn the set tomorrow on my flight and meet up with the guys. They won’t miss a show.”

On my flight the next morning, I listened to their setlist in my headphones over and over, trying to visualize what it would feel like to sit at the drums and play the songs (while scribbling “Verse/Chorus/Bridge/Chorus” song-structure maps in my notebook so I could memorize how they went).

I landed in Seattle and took a cab to meet the band in the parking lot of El Corazon, the club they were scheduled to play that night. We immediately clicked as friends as we loaded the gear inside, ran through their set once at soundcheck, and I thoroughly enjoyed being their drummer for the following month.

To this day, we’ll run into each other now and then as we’re playing European festivals, and talk about it being one of the most fun tours any of us have ever done.

Check out what a great time we had here:

Looking back, I can’t help but think that it was the same thought processes that got me through high school and my teenage years of playing music: putting one foot in front of the other, creating manageable expectations of growth for myself, and applying that to checking off a “bucket list” of musical goals I wanted to accomplish.

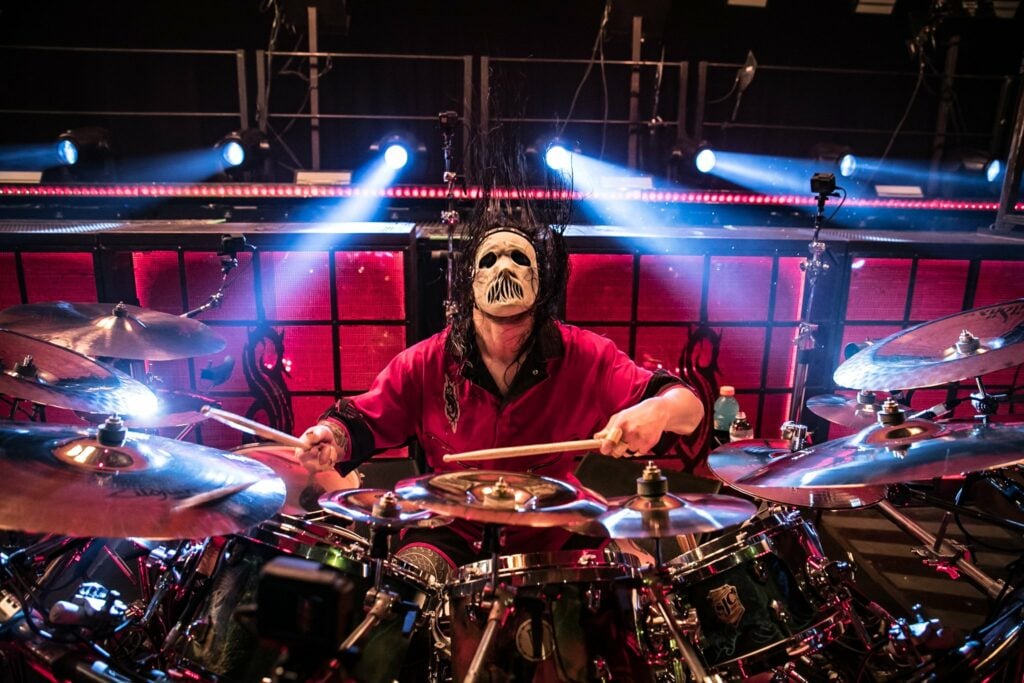

Ultimately, these experiences led me to what’s revealed itself as the single most challenging, rewarding, and fulfilling undertaking of my life. I joined Slipknot in December of 2013, immediately after completing my Bachelor’s Degree in Business & Technology with Honors from Stevens.

I had to combine every lesson I had ever learned throughout all of these musical endeavors, as well as push myself further and harder than I ever thought possible.

I auditioned for the band without any advance preparation, strictly drawing from my muscle memory of when I was in my basement playing along to their records, teaching myself how to play this style of music that spoke to me on a profound level.

Since I had no time to prepare, I presumed they didn’t expect me to play the songs perfectly out of the gate. I also felt they wouldn’t want to have to “coach” someone to be their drummer, or to teach them what Slipknot stands for, or to lead them by the hand.

I figured they would want a drummer who knew the deal, who could come in and school it, and to move forward. That’s the kind of drummer I felt the band deserved — and I would do everything within my control to be that drummer.

I needed to make them comfortable in an otherwise uncomfortable situation: bringing a new guy (albeit a friend they’ve known since his childhood) into their band that’s existed for 18 years and accomplished so much. It was a lot of responsibility — to approach such a heavy moment with care and respect — but to also show up and kick the door down.

Of course, our friendship was 13 years in at this point, and they’d kept tabs on my drumming activity during that time, but we never really discussed it when I’d come see them play.

“Do you know any of our songs?” they asked at my audition.

We played about 20 songs right then and there. It would have been a little rough, but I’m fairly confident we could have played a show that night.

It was instant magnetism, once again.

After a few days of jamming and a discussion amongst themselves, they came to me and said, “Well, you’re the drummer in Slipknot. Go home, enjoy the holidays, and say bye to your friends and family — we start working on the record January 2nd.”

That would become my first album with the band, .5: The Gray Chapter.

As daunting and intense as my initial trials were, we’ve now been together for nine years, made three albums, and played hundreds of shows around the world. I’m still finding ways to dig deeper, and to push my contribution to what we do much further than I could when I first joined. More than anything, I’m proud of that forward motion, because it’s an indication that my original approach to music — setting small, realistic goals for myself — still applies today.

It was 20 years ago that I first thought, “It’d be fun to start playing an instrument.” Spending the last two decades focused on having fun and working hard, playing drums still gives me the same sense of purpose and fulfillment as it did when I picked up my first pair of sticks.

As far as advice for anyone who’s interested in — or who’s just started — playing music? Dream big and aspire to push your music as far as it can go, setting bite-sized, realistic, attainable goals for yourself all along the way.

Once you’ve met those goals, take what you’ve learned and set new ones. You’ll soon discover that the desire to push yourself beyond your capabilities never ends.

You’ll grow, and by enjoying all the little steps it takes to reach your aspirations, hopefully you’ll keep wanting to grow. I’ve been doing so for 18 years — and it still feels like I’m just getting started.

One foot in front of the other…

About the author: Jay is currently on tour with Slipknot, supporting their latest full-length album The End, So Far, and has received the recognitions ‘Metal Drummer of the Year’ and ‘Drum Recording of the Year’ in the 2021 and 2022 Drumeo Awards.

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »