One of the questions I hear the most is how to get a good sound in a recording studio.

It was my early experiences that formed and gave me the ammunition I use today. Let me give you an idea of what studios were like in those days.

In the 60s and 70s, unless you were wealthy enough to buy a Revox tape recorder or hire session musicians (and record on a 4-track machine in the basement of a music store on Denmark Street in London), it was normal to go into a session without a demo of the tune you’d be recording.

This was the case when I recorded Sin After Sin with Judas Priest.

Prior to going into Ramport Studios in Battersea, London, we rehearsed for a day or two. As there were no demos to listen to, Glen Tipton would start playing the song and Ian Hill and I would join in. When it was time for the next section we’d stop and Glen would say “All right, the next bit goes like this!” And off he’d start again. Ian and I would join in and we’d play up to the next section.

Once we knew all the sections, we’d play the whole song and Rob Halford and KK would join us. Then we moved on to the next tune. I don’t remember writing anything down, but maybe I did.

As there were no demos to listen to, Glen Tipton would start playing the song and Ian Hill and I would join in.

When we started recording, Glen Tipton was set up to my left with a thin BBC type baffle (gobo) between us, my Ludwig Octoplus kit in the center, and another baffle and Ian Hill to my right. Glen had a full array of Marshall cabs and Ian had one or two Acoustic 360 cabinets. When they played, my snares would rattle like crazy. The word “isolation” hadn’t been invented yet!

Rob Halford was in the vocal booth, which we would walk through to get to the control room where K.K. was sitting with producer Roger Glover and the engineer.

That is generally how we’d make rock and roll records.

And by the way, we did not call it heavy metal in those days. It was ‘heavy rock’.

In 1976, I was booked into Olympic Studio 2 with Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice to record the original music of Evita.

I was only 19, but I was already very into sound and tones and microphones. As a visiting musician, I had the benefit of hearing all the studios around London and comparing them to each other.

Most studios had the same headphones: those square, black and white DT100 Beyers (which I still use today).

But not Olympic Studios.

They had these awful headphones, made of something that looked like Red Bakelite and tough vinyl gray ear pads with two strands of wire over the top to hold them on your head. I nicknamed the studio “Bomber Command”. Those phones would not have been out of place in a Lancaster bomber in WWII.

They had these awful headphones, made of something that looked like Red Bakelite and tough vinyl gray ear pads with two strands of wire over the top to hold them on your head.

They only had one mono Quad 405 amplifier for the foldback system. Musicians rely on what they hear to get results in the studio, so if you don’t get a good mix you are going to be in big trouble.

This wasn’t a 3-hour session or a jingle where you could just about put up with the foldback system. We were going to be recording for 6 weeks. I said to the engineer, “The foldback sounds terrible. Any chance we could get some Beyer DT100s and another amp to make the foldback stereo?”

“We can’t do that,” the engineer replied.

One of the sayings I hate in life is “We can’t do that!” I persisted.

“All you need is another Quad 405. Put it on the shelf next to the existing one,” I said. “You can use another send that I can see on the console. Some cable, soldering iron, whatever it takes, figure it out. And we want DT100s.”

Andrew and Tim – bless them – said, “Right. Sessions stop until we get these guys a decent headphone system.”

The next day we had brand new Beyer DT100s and a second Quad amplifier, and they’d figured out the wiring so we had a stereo foldback. We may not have had separate mixes like everybody has these days, but all of a sudden, Olympic 2 was great.

Of course, to get good headphone sounds, you have to have good sounds in the first place.

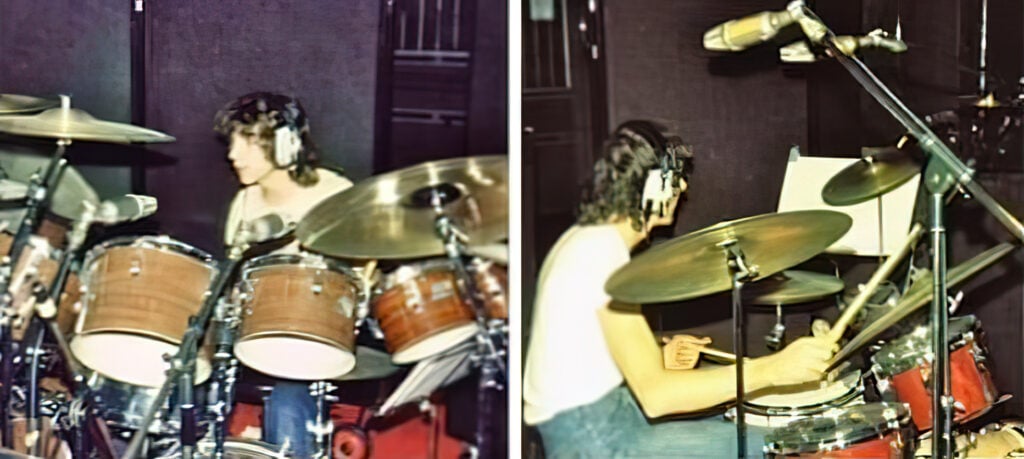

Getting a great drum sound was all about discovery. I didn’t know how to get my drums in the control room to sound the way the drums did on my favorite records. There was so much to learn.

Going back to 1975, I had left Jesus Christ Superstar and the band I was in disbanded and suddenly I was on my own, sitting at home, thinking about where I was going to earn my next paycheck. Slowly but surely, the phone started to ring.

At that point I had one drum kit I used for recording. It was a white Ludwig Big Beat outfit and it had a 22” bass drum, two 13” rack toms and two 16” floor toms. The first of three sessions of the day would be at 10 am and I’d drive to the studio and set up the drum kit.

The engineers would say “the toms are a bit ringy” and I didn’t know whether to tune them high or low.

So, I’d put tape on them.

The classic request in those days was to slacken the snare drum head and put a wallet on it. I hated that sound. I liked a tight, funky snare sound. James Brown, Earth Wind & Fire, and Isaac Hayes – that was the sound I wanted. But it was the disco era of the ‘70s and people wanted this soggy snare drum sound.

I’d finish the session, leave the tape on the toms, drive my drums across London and set them up for the next session.

“Hmm. The toms are a bit ringy.” The next engineer would say.

“Oh.”

I’d put another piece of tape on them.

After three sessions, I’d have three pieces of tape on each drum. Something wasn’t right. I didn’t like the sound anyway, so at the end of each session I would rip off all the tape and start again from scratch.

I soon stopped putting more than one strip of tape on the toms.

After three sessions, I’d have three pieces of tape on each drum. Something wasn’t right.

The bass drum was pretty easy to manage in those days because we didn’t use a front head. All we had to do was stop the lugs from rattling. So, I took each lug off, stuffed a small piece of foam inside, then bolted them back on. The studio would use a piano canvas cover for the inside of the bass drum and weigh it down with a heavy weight or sandbag.

As for the snare drum, well, some engineers liked the way I tuned it and some didn’t.

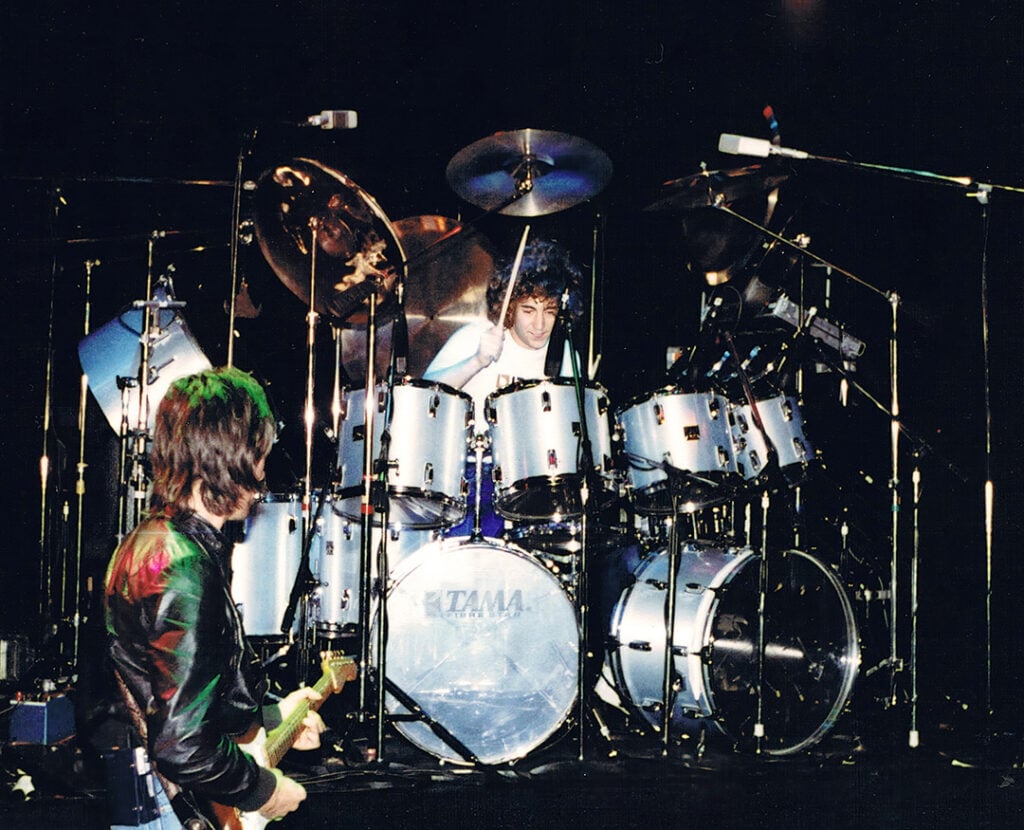

But the tom toms…we had only just started using tom mics. Most of the time we just had two overheads, snare, and kick. The engineers didn’t have isolated sounds to deal with, so they always had a certain amount of spill since everyone would play through amplifiers. It was hard to hear the toms in the mix because they were kind of an afterthought.

Even after taping the toms, I’d still get comments about them being too ringy. I started tuning them up, and I started playing differently. I made sure that whenever I hit a tom-tom, I hit it hard. I made sure nothing else was in the way. I’d stop playing the kick drum and try to keep the groove going but not necessarily keep the playing going.

I hear so many drummers who keep everything going; they’ll hit the kick drum while hitting the floor tom. Acoustically it might sound okay, but in a recording scenario two low pitched sounds tend to cancel each other out once played back through a pair of speakers. It sounds clumsy and it’s too much for the speaker to handle.

You have to think like the listener rather than the player. You’ve got to start changing the way you play.

I stopped getting complaints about the tom-toms.

I was doing another session at the end of 1975 at a studio called Trident, one of those special rock and roll studios where Bowie, Elton John, Queen, John McLaughlin and loads of people worked. I didn’t dig the snare sound – they were using a Sony C37 mic that a lot of American studios used at the time – but the kick drum sound was glorious.

I went upstairs to listen to the playback. I think the engineer was so concerned about this bloody snare drum sound (that I hated anyway), he forgot about the rest of the drum kit and just put the faders up. There was this other guy there who came up to me and said, “Your tom-tom sound is amazing.”

“Oh, really?”

Turns out this guy was Clive Franks who was Elton John’s live sound engineer for years. Not only did he engineer Elton, he also did Toto, Robert Plant, Peter Gabriel, and eventually The Who.

Wow. Suddenly I’m vilified. There’s my tom-tom sound!

That gave me the confidence I needed. It worked – it actually worked. That was the turning point of the sound I’m now known for.

Nothing comes easy and nothing comes quickly, but you’ve got to keep thinking about it. I’d do a session and go, “Shit, it sounded awful today – what was it? What can I do to change things?” This went on for years until I started cracking the puzzle.

Use the process of elimination. Learn everything you can about your equipment and the gear being used to record it. Can you tighten or loosen something?

And most importantly…are you playing in a way that makes your drums sound the best they can sound?

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »