This Funk/Soul Guide is actually a full chapter pulled directly from The Drummer’s Toolbox: The Ultimate Guide To Learning 101 Drumming Styles.

We wanted to quickly show you the incredible value that’s inside the book, plus share a quick video that highlights the quality of the print.

This isn’t your ordinary drum book. The Drummer’s Toolbox is bound to sit flat for music stands or wherever else, you’ll get 450+ full color pages, and it’s all pulled together to help you develop your own unique style on the drums.

Soul and funk dominated the music world during the 1960s and 1970s. Record labels like Motown Records and Stax Records, artists like Stevie Wonder, James Brown, and Marvin Gaye, and the unforgettable sounds of iconic rhythm sections like the Funk Brothers and Booker T. & The M.G.’s all created so much magic it’s no wonder these two genres were so successful and influential.

Playing soul and funk on the drums just might be the most fun you’ll ever have—especially because there are so many unique types of grooves used in each specific subgenre of this music. Funk drumming, in particular, is a favorite among most drummers. I personally love it because the drums, along with the electric bass, play one of the most important and dominant roles in the style.

If you’ve developed fundamental skills through rock, jazz, blues, and/or country drumming, soul and funk drumming will incorporate and expand on those skills. The drumming styles in this chapter feature shuffle patterns, snare drum grooves, quarter, eighth, and sixteenth note grooves, as well as grooves played with straight and swing feels.

These two genres of popular music emerged during the late 1950s (soul) and mid-1960s (funk). Both styles were predominantly played by African-American musicians during these years. Although the styles vary wildly from one another, I cover them together in one chapter here because funk music was first created and popularized by soul musicians—notably James Brown. Many prominent soul artists of the 1960s and 1970s, like Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, also crossed over and experimented with funk music throughout their careers. As you’ll learn, soul and funk drumming are quite different from one another, but the ties between these two genres make them soul sisters. Or Funk Brothers. Whatever. You know what I mean.

Soul music, which only emerged a few years prior to funk music, emphasizes lyrics, vocal melodies, and vocal harmonies. This style is essentially secularized gospel music featuring “catchy” melodies and call-and-response vocals. Soul music is much less complex than funk music and was more commercially successful. But during the early 1970s, the popularity of soul music quickly faded as funk music became the more prominent genre. Funk music emerged from jazz, blues, and soul music during the mid-1960s and became one of the first styles of music to place more emphasis on rhythm than melody and harmony. The rhythm section is the driving force of funk music. Some identifying characteristics of this style include syncopation and extended harmony (commonly used in styles of jazz like bebop).

Soul drumming and funk drumming are quite distinct from one another. In general, funk drumming is much more complex and syncopated in comparison to soul drumming. Remember, the rhythm section plays a dominant role in this style, so they have the freedom to play more complex parts. Funk drumming (and other styles related to funk) often incorporates linear patterns, ghost notes, hi-hat openings, and syncopated lead hand patterns. Because soul is vocal-focused music, the drums only play a supporting role in this style. This means soul drumming features more basic patterns with fewer embellishments.

Learning how to play soul and funk music on the drums will benefit you in two significant ways. Soul drumming will teach you how to be disciplined and how to lay down a solid groove for the duration of an entire track. On the other hand, funk drumming will teach you how to add some flare to your drum grooves by exploring different ways to embellish them. These are both very important skills that will apply to any style of music you play on the drums. By the time you complete this chapter, you’ll also know how to differentiate soul and funk grooves from one another so that you never accidently play a linear David Garibaldi groove in a Motown tune.

In this chapter, you’ll first learn about one drumming style that had a significant impact on the development of soul music, then you’ll dive into three specific soul drumming styles. Next, you’ll focus on funk music. You’ll learn about one drumming style that had a significant impact on the development of funk music, and then you’ll explore four more specific funk drumming styles. Lastly, you’ll focus on one final drumming style that has been impacted by both soul and funk.

One style that played an important role in the development of soul was gospel music. For me, having played gospel music and contemporary worship music (a popular subgenre of gospel that’s included in the Appendix of The Drummer’s Toolbox) in many different churches over the past fifteen years, this drumming style has benefited my drumming in countless ways. This genre of music taught me the importance of dynamic control, listening to the musicians you’re playing with, and being aware of your audience (or congregation in this case). Many of the grooves I’ve learned from this drumming style have also transferred directly into many other styles of music that I play, like rock and country.

Musicians have been playing gospel music in Christian churches for hundreds of years, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that drummers were featured. During the 1950s, gospel music was also being influenced by other styles of music that were prominent at the time, like rock and roll, R&B, and country music. Some of the best-known gospel musicians in history include Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke, Kirk Franklin, and Yolanda Adams.

Like many other styles, gospel drumming can be played with a straight or swing feel and at a variety of different tempos. Like “Swung 12/8 Blues”, this is a drumming style that frequently incorporates swung sixteenth notes. However, in this section, you’ll need to know how to interpret straight sixteenth notes as swung sixteenth notes. I’ll explain this concept soon. When it comes to specific techniques in gospel drumming, cross-sticking and hi-hat openings are two of the most essential. In this section, you’ll learn a number of different grooves that incorporate both of these techniques.

This groove is played by Erick Morgan in the song “Whatcha Lookin’ 4” by Kirk Franklin & the Family. When you listen to the recording, you’ll notice that this groove is played with a swing feel. You can hear him play it in the song at 0:17. (Quarter note=96 BPM)

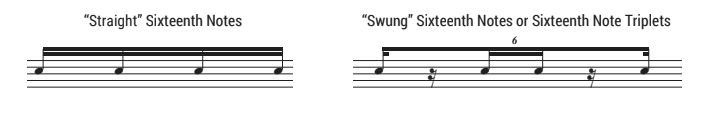

Before you start with the hi-hat pattern, you need to understand how to interpret straight sixteenth notes as swung sixteenth notes. Throughout the previous chapters, you’ve interpreted eighth notes as eighth note triplets when playing with a swing feel. In this case, you’ll be interpreting sixteenth notes as sixteenth note triplets, also known as sextuplets. Here’s what this looks like in notation:

Now, try playing one full measure of straight sixteenth notes followed by one full measure of swung sixteenth notes like this:

Just like how you would interpret eighth notes as eighth note triplets, you should notice a dramatic difference between the sound of straight and swung sixteenth notes.

Now that you know how to interpret sixteenth notes as sixteenth note triplets, start by isolating the hi-hat pattern.

Next, add in the snare drum pattern.

Lastly, add in the bass drum and make sure that everything is swingin’.

This is another swung sixteenth note beat that can be used in gospel music. One of my greatest influences, Larnell Lewis of Snarky Puppy, demonstrates this pattern in his Drumeo course titled “Gospel Drumming”. (Q=105 BPM)

Bernard Purdie, the inventor of the “Purdie Shuffle”, plays this two-bar phrase in a live performance of “How I Got Over” by Aretha Franklin. This particular live performance was released on her Amazing Grace record in 1972. This two-bar phrase could be used in many rock contexts as well. Listen to him play this pattern in the live recording at 0:19. (Q=163 BPM)

Here’s an example that incorporates cross-sticking. (Q=75 BPM)

Here’s another eighth note gospel groove that could be used in many rock and country settings as well. (Q=100 BPM)

This last example is used in a style of gospel music known as shout music. This style is played at fast tempos and emphasizes the upbeats. (Q=150 BPM)

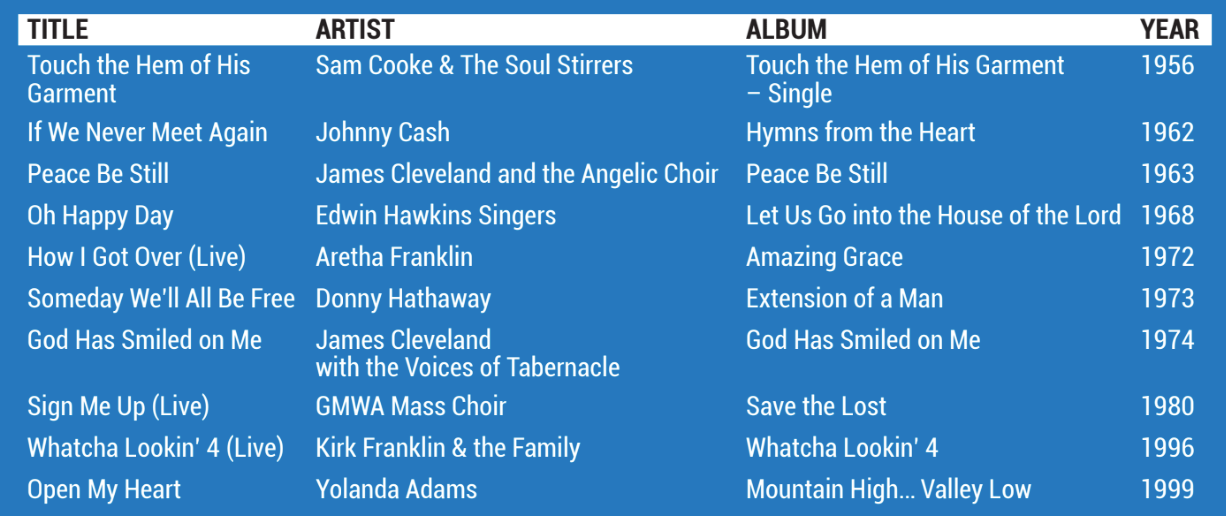

Here are ten gospel recordings that focus on mid-to-late twentieth century gospel music. If you’re a drummer who plays contemporary worship music in your church, it’s important to understand how gospel music has evolved over the decades into the contemporary styles being played today. When you listen to these recordings, focus on how gospel drumming has developed and changed over the decades. What do you notice about the drum grooves played in the 1950s and 1960s compared to the drum grooves played in the 1990s?

During the 1960s, one record company was responsible for producing the most successful soul albums and singles in the United States: Motown Records.

Motown Records was founded in Detroit, Michigan in 1959 and became known for its signature “Motown Sound”. The majority of Motown’s music was recorded by a group of studio musicians known as the Funk Brothers. These studio musicians would record an instrumental backing track first, and then the featured vocalist or group of vocalists would overdub their vocal parts. The Funk Brothers were undoubtedly the secret behind the legendary “Motown Sound”.

This style of soul music often features strings and horns, gospel-influenced vocals, overdubbing of various instruments, and a consistent quarter note pulse that is outlined by the bass and drums. Some Motown recordings even featured two drummers. Some of the most famous names in Motown are the Temptations, Diana Ross, the Jackson 5, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, and the Four Tops.

While there are many unique grooves used in this drumming style, you need to know a few essential ones to get started. The most iconic groove in Motown music features snare drum backbeats on every quarter note. Even though you can hear this snare drum pattern used in other drumming styles like rock and metal, it’s a defining characteristic of Motown drumming. This type of groove outlines the steady quarter note pulse of Motown music. In this section, you’ll also learn some other quarter, eighth, and eighth note triplet-based grooves used in this style.

Session drummer Richard “Pistol” Allen performs this classic Motown beat throughout the song “It’s the Same Old Song” by the Four Tops. Notice how the snare drum is played on every downbeat throughout the measure. This iconic groove is heard on countless Motown recordings. (Q=128 BPM)

Start by playing steady eighth notes on the hi-hats.

Next, add in the snare drum.

Lastly, add in the bass drum on the “&” of beat three and four.

This is a variation of the previous groove with a different bass drum pattern. (Q=140 BPM)

Uriel Jones, another Motown session drummer, plays this groove in the song “Twenty-Five Miles” by Edwin Starr. You can hear this groove in the recording at 0:26. (Q=128 BPM)

Quarter note grooves like this one are also popular in Motown music. (Q=150 BPM)

Gene Pello plays this groove in the song “The Love You Save” by the Jackson 5. You can hear him play it in the recording at 0:09. (Q=171 BPM)

Shuffle patterns like this are also commonly used in Motown music. (Q=130 BPM)

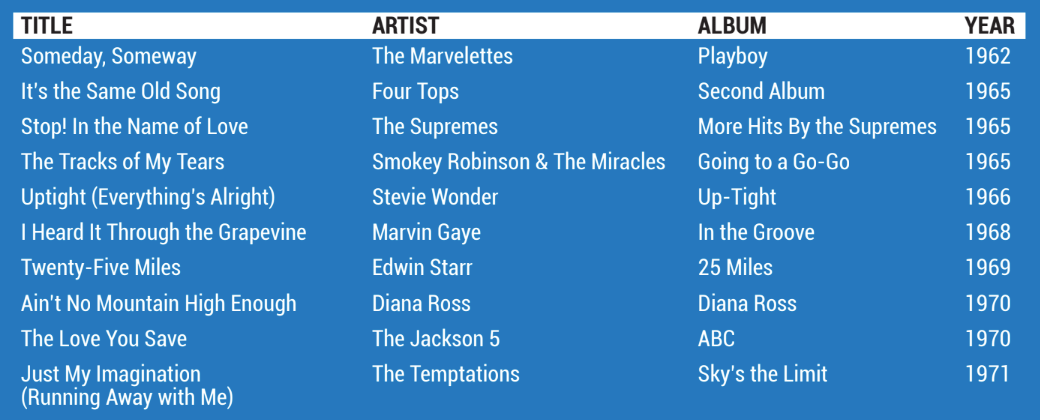

In this list, you’ll find ten classic recordings from Motown’s most successful years. When you listen to these recordings, notice how most of them feature the same eighth note drum groove with snare drum backbeats played on every quarter note. This drum groove is an essential part of the “Motown Sound”. Some of these recordings feature the same drum groove for the entire duration of a song. When you play along with recordings like this, stay focused and strive to play the same groove throughout the entire track, just like Motown session drummers did.

Just as the “Motown Sound” was developing in Detroit during the 1960s, another style of soul music, boogaloo, was emerging in New York City.

Boogaloo—also known as bugalú or Latin soul—originated in New York City during the early to mid-1960s. This genre of music fuses elements of blues and soul with elements of Afro-Cuban styles like mambo and guaguancó. Boogaloo was mainly played by Latin American teenagers who lived in New York City and were therefore exposed to a vast array of music—everything from American styles like jump blues and soul to more traditional Afro-Cuban and Afro-Caribbean styles. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, musicians also began to merge elements of boogaloo with jazz and funk music. Ray Barretto, Pérez Prado, Joe Cuba, and Pete Rodríguez were some of the leading boogaloo artists during the 1960s. Even though the popularity of boogaloo had diminished by the early 1970s with the introduction of salsa (which you’ll learn about in Chapter 10 of The Drummer’s Toolbox), musicians have continued to adopt elements of boogaloo into other genres of music, as you’ll hear in the recommended listening list.

The drum grooves played in boogaloo music often accentuate the percussion, piano, and/or bass parts in the music. More specifically, the snare drum pattern often follows the rhythm of the percussion or piano parts, and the bass drum follows the rhythm of the bass guitar. When you listen to the boogaloo recordings in this section, you’ll hear what I mean. Boogaloo grooves often incorporate snare drum and bass drum displacement, ghost notes, and hi-hat openings as well.

Orestes Vilató plays this groove throughout the song “New York Soul” by Ray Barretto. Notice how the bass drum and snare drum patterns are based on some of the rhythmic patterns played by the pianist in the recording. (Q=133 BPM)

Start by playing quarter notes on the hi-hats.

Then, add in the snare drum pattern.

Finally, add in the bass drum pattern.

This groove incorporates ghost notes, a hi-hat opening, and some rhythmic displacement on the “&”s of beat three and four. (Q=120 BPM)

Leo Morris performs this groove throughout the song “Alligator Bogaloo” by Lou Donaldson. This song is a perfect example of how boogaloo grooves can be played in a jazz context. You can hear this groove being played right at the beginning of the tune. (Q=129 BPM)

Here’s a groove that incorporates three snare drum backbeats. (Q=120 BPM)

Stanton Moore performs this groove in his song “Boogaloo Boogie”. This example is notated in sixteenth note triplets, which is the same subdivision used to notate swung sixteenth notes. You can hear this groove in the recording at 0:06. (Q=117 BPM)

Here’s another example that’s played on the ride cymbal. (Q=120 BPM)

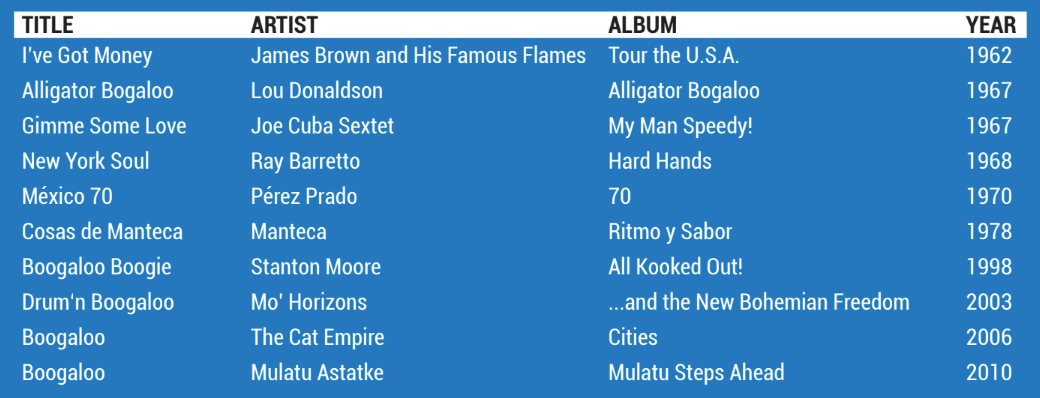

Here are ten recordings that will help you become familiar with boogaloo drumming. In this list, I’ve included some traditional boogaloo examples as well as some other examples that span a variety of different genres so that you can hear how boogaloo drum grooves have been incorporated into them. Listen to these recordings and focus, specifically, on the relationship between the bass drum and snare drum and the patterns played by other instruments in the rhythm section. As you’re listening, pay attention to how the ghost note patterns are played by different drummers, as ghost notes are an essential element of most boogaloo drum grooves.

In the late 1980s, more than two decades after the development of boogaloo music, a new style of soul music emerged in the United States and the United Kingdom: neo-soul.

The term “neo-soul” was invented by Kedar Massenburg, a record producer who was the president of Motown Records from 1997 to 2004. Neo-soul is a contemporary style of soul music with influences ranging from jazz and funk to hip-hop and electronic music. This style often features female vocals, as well as acoustic and digitally programmed instruments. You can think of neo-soul like 1960s Motown music being played three decades later with the incorporation of modern music technology and lyrical content. Some of the most successful and influential neo-soul artists in history include Erykah Badu, Maxwell, Lauryn Hill, D’Angelo, and Jill Scott.

Neo-soul drumming is all about having a relaxed, laid-back feel. Neo-soul is usually played at medium to slow tempos, which gives the music its chilled-out vibe. When you listen to this style of music, you’ll notice that some songs feature acoustic drums while others feature programmed drums. This means that sometimes you’ll be trying to emulate a drum machine (a concept that you’ll explore further in Chapter 7 of The Drummer’s Toolbox). One drummer who has mastered this skill is Ahmir “?uestlove” Thompson. I was first introduced to him while watching his band, The Roots, perform on the late-night talk show, Late Night With Jimmy Fallon. Go check out some of his drumming. You’ll be glad you did!

This style features music that’s played with both straight and swing feels. For each groove, I’ve indicated which feel you should use. You should also practice each exercise with both straight and swing feels for an added challenge.

This beat was programmed by Bob Power and can be heard in the song “On & On” by Erykah Badu. This groove should be played with a slight swing feel as you’ll hear on the recording. You can hear this beat in the recording at 0:03. (Q=80 BPM)

Start by playing steady eighth notes on the ride cymbal.

Now, add in the cross-stick pattern.

Lastly, add in the bass drum pattern to complete the groove. Like some of the examples in the “Go-Go” section, the sixteenth note figures (which all involve the bass drum) in this groove should be played as swung sixteenth notes.

This type of groove is played at slower tempos with both straight and swing feels. Try them both out. (Q=70 BPM)

Here’s another example that features cross-sticking and a hi-hat opening. This example should be played with a swing feel. (Q=70 BPM)

Here’s a one-handed sixteenth note groove that should be played with a straight feel. (Q=70 BPM)

Ahmir “?uestlove” Thompson plays this 6/8 groove in the song “Send It On” by D’Angelo. When you practice this groove, try to emulate the same swing feel that “?uestlove” demonstrates in the song. Listen to it in the recording at 0:06. (E=129 or D.Q=43 BPM)

This groove incorporates two hi-hat openings and is more syncopated than the previous grooves you’ve learned. Try playing this groove with a straight feel. (Q=70 BPM)

These neo-soul recordings will help you become familiar with this drumming style. When you listen to these songs, first try to determine whether the drums are programmed or being played by a live drummer. Then, listen for the use of techniques like cross-sticking and hi-hat openings. Do you hear these techniques throughout entire songs or are they only used during specific sections? When you play along with these recordings, really focus on maintaining a relaxed feel. This is one of the most important elements of neo-soul drumming.

Just as gospel music played an important role in the development of soul music, one drumming style that played an important role in the development of funk was New Orleans second line drumming. This style of drumming originated in New Orleans and was featured in second line parades.

Second line parades are a New Orleans tradition dating back to the 1800s. They had a huge impact on the development of jazz, funk, and rock and roll music. These parades took place before and immediately following a funeral. These parades had two separate “lines”. The family of the deceased, the brass band, and the hearse were in the first line, while the snare drummers, bass drummers, dancers, and supporters were in the second line. On the way to the burial site, the first line would play slow, somber music—songs like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”. After the funeral, a celebratory procession would begin with the second line playing and dancing to songs like “When the Saints Go Marching In”.

This drumming style is played with a swing feel and incorporates the son clave pattern (and variations of it). We can modify the common 3:2 pattern into the 2:3 son clave by playing the “two-side” of the clave first. Here’s what this looks like:

Both the 2:3 and the 3:2 son clave can be used in second line drumming.

This drumming style was originally performed by bass drummers and snare drummers, but over the years these traditional patterns have been adapted for the drum set. To maintain an authentic sound, the snare drum grooves you’ll learn in this section will only incorporate the snare drum, bass drum, and hi-hats.

Fred Staehle plays this groove starting at the very beginning of the song “Iko Iko” by Dr. John. Notice how clearly the son clave pattern is outlined. This groove is very similar to the “Bo Diddley Beat”, which you can find in Chapter 1 of The Drummer’s Toolbox. (Q=165 BPM)

Start with the snare drum pattern. Remember to swing the eighth notes.

Then, add in the bass drum and the hi-hat foot.

This is an example of a traditional second line snare drum beat. Instead of playing a double stroke like in the previous example, play these rolls as buzz strokes. For more information and a demonstration of how to play these buzz strokes in a second line context, check out the live lesson titled “U.S. Roots—Traditional Second-Line Snare Beats” with Pat Petrillo on Drumeo. (Q=165 BPM)

Here’s a variation that’s based on the 2:3 son clave. (Q=165 BPM)

This is a variation of the previous example. You’ll notice that the snare drum and bass drum patterns are slightly different. (Q=165 BPM)

Funk legend Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste plays this groove in the song “Hey Pocky A-Way” by The Meters. All of the accented notes will be played with your lead hand. (Q=171 BPM)

This groove incorporates some accented flams. (Q=165 BPM)

The recordings here will introduce you to second line drumming. There are examples by rock and roll, jazz, and funk artists so that you can hear how this style of drumming has influenced all three of these distinct musical genres. Listen to these recordings and try to identify which clave patterns are used in each song. Is the clave pattern being accented on the snare drum or being played on the bass drum? Is the complete clave pattern being outlined or is a variation of the pattern being used?

Now that you’ve developed a solid foundation in soul drumming, it’s time to transition to funk drumming.

I can remember being about thirteen years old when my school band director brought an arrangement of Herbie Hancock’s funk standard “Chameleon” to a rehearsal. It blew my mind! I went home after that rehearsal and immediately checked out the original recording from Herbie’s Head Hunters record. I had never heard anything like what Harvey Mason was playing on this funk track. It was syncopated, it had some displaced backbeats, and it was just downright intriguing. Let’s just say, having the opportunity to watch Harvey Mason perform his arrangement of “Chameleon” when he came to Drumeo was a pretty incredible experience. You can witness the same performance that I did by checking out his Drumeo live lesson.

Funk developed during the mid-1960s as a hybrid of soul, jazz, and blues music. By the 1970s, funk had eclipsed soul music in the United States. As I mentioned in the chapter introduction, this was one of the first styles of music to place more emphasis on rhythm than melody and harmony. The key innovator of funk music during the 1960s was James Brown, who began his career in the 1950s as a soul musician. Largely thanks to Brown’s innovations, funk music brought rhythm section players off of the sidelines and into the musical spotlight. This style is known for featuring “slap” bass, guitar effects like “wah-wah”, horn sections, and syncopated drum grooves. Harmonically, funk music is also much more complex than soul music. Some of the most famous funk bands and artists of all time include the Meters, Sly and the Family Stone, Parliament, Funkadelic, and Tower of Power—and of course James Brown.

Funk drumming often features syncopation and rhythmic displacement, rudiment-based hand patterns, hi-hat openings, ghost notes, and linear patterns (where no two limbs play at the same time). All of the grooves in this section will incorporate one or more of these unique elements. When you play these grooves, you need to make sure that they sound “funky”. If you’re not dancing in your seat, they’re not funky enough.

Funk legend David Garibaldi performs this groove at the very beginning of “Squib Cakes” by Tower of Power. This is one of the most recognizable funk grooves of all time. At Drumeo we had the privilege of David Garibaldi visiting our studio to film some lessons. If you want to dive deeper into his playing and some of the concepts that he uses to create these types of grooves, you can check out his live lesson above titled “Building Coordination” and his Drumeo course titled “The Funky Foot”. (Q=114 BPM)

Start with the hi-hat pattern.

Next, add in the snare drum pattern. Remember that there should be a distinct difference between the dynamic level of your ghost notes and backbeats.

Lastly, add in the bass drum pattern.

In this example, the first snare drum backbeat is played on the “a” of beat one. (Q=115 BPM)

Here’s an example of a linear funk groove. Notice how no two limbs are playing at the same time. (Q=100 BPM)

In this groove, your hands will play a single paradiddle over top of a syncopated bass drum pattern. (Q=100 BPM)

The late great Clyde Stubblefield plays this legendary groove in the song “Funky Drummer” by James Brown. This groove has been sampled in over 1400 songs since its original release in 1970, making it one of, if not the most, sampled song in history. Listen to this groove in the recording at 5:22. (Q=98 BPM)

This final groove is played on the ride cymbal. (Q=115 BPM)

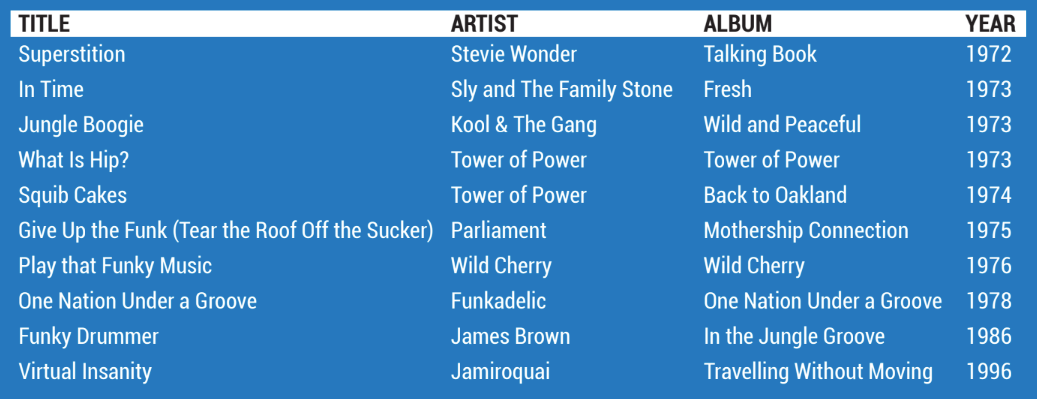

Here are ten funk recordings that every drummer should check out. Many of the grooves demonstrated here feature elements like syncopation, displacement, hi-hat openings, and ghost notes. A few of these recordings also demonstrate how funk grooves can be played with a swing feel. Enjoy these recordings, and listen specifically for the elements that are demonstrated by different funk drummers on each recording.

During the 1960s and 1970s, musicians in New Orleans were playing funk music that was different from other funk music in the United States.

The biggest difference between New Orleans funk and other funk music was the drumming. Drummers playing New Orleans funk weren’t just playing grooves with straight and swing feels…they were often playing “in between the cracks”, as Stanton Moore calls it. This means they were playing somewhere in between straight and swung. New Orleans funk also incorporates rhythmic patterns used in New Orleans second line drumming, like the son clave pattern. Even though there are many bands and artists that played New Orleans funk, The Meters are considered the most influential New Orleans funk band in history.

While the grooves in this section may just seem like another batch of funk grooves, this drumming style isn’t simply about the notes being played, it’s really about the overall feel—playing with a straight feel, swing feel, or the elusive “in between the cracks” feel. The only way to learn how to play this “in between” feel is to simply listen to the master himself, Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste, and try to emulate the way he’s playing. This is no easy task, but it’s worth the investment. Before you play each groove in this section, make a clear decision about how you want the groove to sound. This will determine which feel you choose: swing, straight, or “in between”. Just like the grooves in the previous section, New Orleans funk drumming also incorporates hi-hat openings, ghost notes, syncopation, and rhythmic displacement.

Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste plays this groove in the song “Look-Ka Py Py” by the Meters. This groove should be played with an “in between” feel, just like “Zigaboo” plays it. You can hear it in the recording at 0:08. (Q=88 BPM)

Start with the hi-hat pattern.

Now, add in the snare drum pattern.

Lastly, add the bass drum pattern.

In this example, the second backbeat is displaced by an eighth note to the “&” of beat four. (Q=100 BPM)

This groove incorporates a unique sixteenth note hi-hat pattern. (Q=90 BPM)

Here’s a groove that will really put your hi-hat foot to work. (Q=90 BPM)

Here’s another “Zigaboo” Modeliste groove from the song “Fire on the Bayou” by The Meters. The bass drum pattern and hi-hat accents in this beat outline the first part of the 3:2 son clave. Check it out in the recording at 0:10. (Q=99 BPM)

It’s also common in New Orleans funk to play the snare drum and bass drum in unison. Here’s a groove that will help you practice this. (Q=90 BPM)

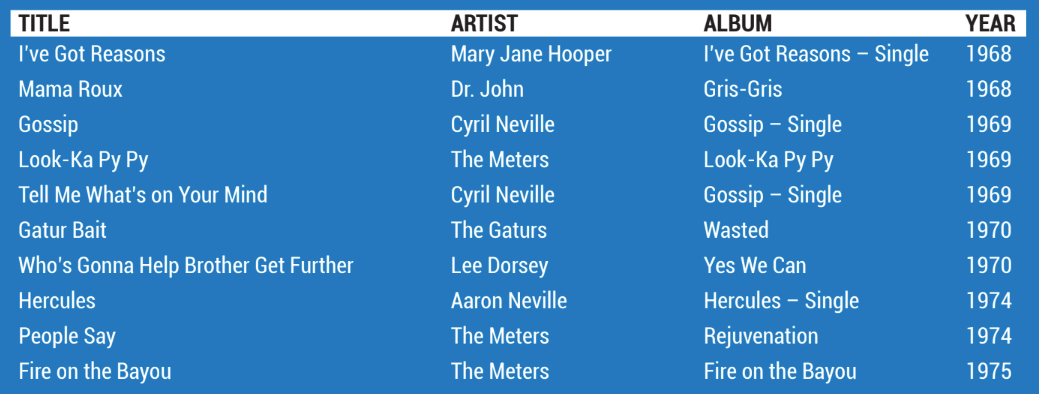

These iconic New Orleans funk recordings will introduce you to this style of drumming. You should focus on two things when listening. First, listen for the influence of second line drumming and standard funk drumming in New Orleans funk drumming. Which elements of these two other drumming styles do you recognize in these recordings? Second, focus on the feel that is demonstrated in each recording. Is the drummer on each recording playing with a swing, straight, or “in between” feel?

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, about a decade after the development of boogaloo, another fusion style of funk music known as Latin funk emerged in New York City.

Just like soul music was fused with Latin music to create boogaloo, funk was now melding with Latin music to create Latin funk. This resulted in funk music that incorporated syncopated Latin rhythms and clave patterns, as well as traditional Latin percussion instruments. Mongo Santamaría, Joe Bataan, Grupo Irakere, and Ray & His Court were some of the leading Latin funk bands and artists during the 1970s.

This drumming style combines funk drumming with elements of Afro-Cuban, Afro-Brazilian, and Afro-Caribbean drumming. If you remember back to the section on boogaloo drumming, I mentioned that New York City was a melting pot of musical styles and influences during the 1960s and 1970s. That’s why Afro-Cuban, Afro-Brazilian, and Afro-Caribbean music were all being fused with funk music during this era. Because you already have a solid understanding of funk drumming, you can get started incorporating some traditional Latin rhythms and clave patterns into some funk grooves. We dive deeper into Latin styles and rhythms in Chapters 8, 9, and 10 of The Drummer’s Toolbox.

This Latin funk groove is played by an uncredited drummer in the song “Mercurio” by Ramón Gil. The bass drum pattern in this groove outlines the Afro-Cuban tumbao pattern. You can listen to it in the recording at 0:24. (Q=106 BPM)

Start by playing the hi-hat pattern. This pattern is similar to hi-hat patterns used in disco music, which you’ll learn about later in this chapter.

Now, add in the snare drum on every downbeat.

Before you add in the bass drum, let’s take a moment to look at the tumbao pattern, which emphasizes the “&” of beat two and the downbeat of beat four like this:

The tumbao pattern can also be notated as a one-bar phrase using eighth notes and sixteenth notes. That looks like this:

Both ways are correct because the emphasized rhythm is the exact same in both examples. The only difference is the note values being used. Now, add in the tumbao bass drum pattern.

The accent pattern in this groove is based on a cowbell pattern used in Afro-Cuban music. (Q=130 BPM)

This groove features the Afro-Cuban cáscara pattern on the hi-hats. This pattern is commonly played by a timbale player. (Q=110 BPM)

In this example, you’ll play the same hand pattern as the previous example, but you’ll also be playing the Afro-Brazilian baião bass drum ostinato. (Q=110 BPM)

Teddy Williams performs this groove in the song “Soul Freedom” by Ray & His Court. The bass drum pattern in this groove outlines a cross-stick pattern played in bossa nova (a style we explore in Chapter 9), with the addition of another bass drum stroke on the “a” of beat two. Check out this groove in the recording at 0:07. (Q=116 BPM)

This last groove is a funk variation of the Afro-Cuban songo pattern (which we explore in Chapter 8). (Q=210 BPM)

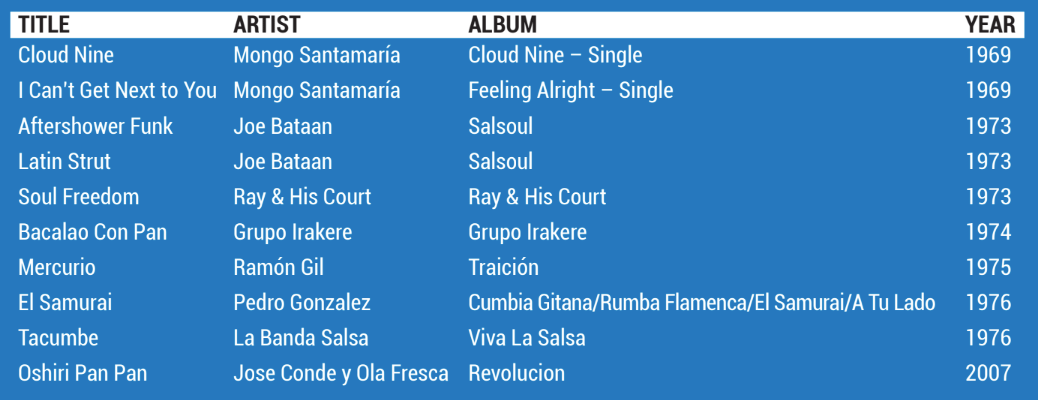

In this list, you’ll find ten recordings that will introduce you to Latin funk music. Because any element of Afro-Cuban, Afro-Brazilian, or Afro-Caribbean music can be fused with funk music, Latin funk is a very broad and diverse style of music. However, there are several key elements to pay attention to when listening to these recordings. Try to identify some of the rhythmic patterns you’ve learned throughout this section. These could be played by the drummer, percussionists, or even another member of the rhythm section. Also, focus on the instrumentation that’s used in Latin funk. What do you hear in these recordings that differs from non-Latin influenced funk music?

Just as Latin funk was developing in New York City, yet another style of funk music was developing in Washington D.C. during the late 1960s and early 1970s. This style was called go-go. Go-go fuses elements of funk, soul, and hip-hop music (which started emerging in the mid to late 1970s). This style regularly features electric guitar, electric bass, keyboards and synthesizers, vocals, horns, drums, and percussion. Some of the most notable go-go artists and bands include Chuck Brown, Trouble Funk, and Experience Unlimited.

One thing you really need to know is that most go-go songs feature a signature drum groove (or variations of it). The most important part of this groove is the bass drum and snare drum pattern. The snare drum is played on beats two and four, and the bass drum is played on beat one, the “&” of beat two, the “&” of beat three, and the “e” of beat four. Here’s what that looks like in notation:

Eighth or sixteenth notes are usually played on the hi-hats as well, often with added embellishments like hi-hat openings and accents. It’s also important to know that in this style, sixteenth note figures are almost always played with a swing feel. As you work through the examples in this section, practice playing every sixteenth note figure with a swing feel, then go back and practice playing every sixteenth note figure with a straight feel as well.

Ricardo D. Wellman plays this groove in the song “Bustin’ Loose” by Chuck Brown & The Soul Searchers. Notice how the bass drum pattern is slightly different in each bar but still follows the basic pattern explained earlier. Check it out in the recording at 0:06. (Q=112 BPM)

First, start with the hi-hat pattern.

Next, add in the bass drum pattern.

Lastly, add in the snare drum on beats two and four.

This is a basic version of a go-go beat with one hi-hat opening on the “&” of beat three. (Q=100 BPM)

This groove features a slightly busier hi-hat pattern as well as an additional bass drum stroke on the “a” of beat four. (Q=100 BPM)

Here’s a variation that’s played on the ride cymbal. (Q=100 BPM)

This groove is played by Emmett Nixon in the song “Hey Fellas” by Trouble Funk. When you play this groove, make sure that each hi-hat opening is played for its correct duration: one is an eighth note and one is a sixteenth note. You can hear this groove in the song at 0:06. (Q=103 BPM)

In this final example, groups of three notes will be played on the hi-hats. Remember to play these as swung sixteenth notes. (Q=100 BPM)

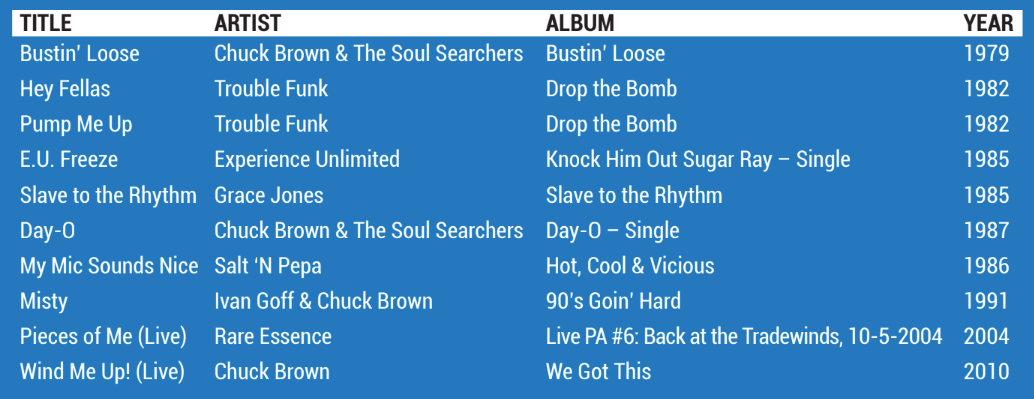

These songs will introduce you to go-go drumming. When you listen to these recordings, focus on the snare drum and bass drum patterns. Do you usually hear the standard snare and bass drum pattern being played or do you usually hear variations of it? Also, pay close attention to how swung sixteenth note figures are played in this style, as this is a key element of go-go drumming that plays an important role in the overall feel of go-go drum grooves.

One of the most popular styles of music to emerge from both soul and funk was disco music. This style started developing in the mid-1960s, but disco became one of the most popular genres of music in the United States during the 1970s.

Disco is a form of dance music that was played in American nightclubs (or discothèques). Many funk and soul artists, like the Jackson 5 and Diana Ross for example, experimented with disco music throughout their careers. This style features similar instrumentation to funk: vocals, keyboards and synthesizers, electric bass, electric guitar, drums, horns, and sometimes even strings and drum machines. Some of the most famous disco bands and artists include the Bee Gees, Gloria Gaynor, Chic, Carl Douglas, and the Village People.

Disco is all about what keeps people dancing, so this drumming style is characterized by a steady quarter note pulse that’s played on the bass drum (“four on the floor” bass drum pattern) and consistent backbeats on the snare drum. The hi-hats also play a significant role in disco drumming. Most disco beats feature hi-hat openings that are played on the upbeats (or the “&”s). Hi-hat openings are used in both eighth note and sixteenth note grooves (the most common subdivisions used in this drumming style). In this section, you’ll learn a variety of disco grooves that are equally foundational to both classic disco and its modern incarnations.

Dennis Bryon plays this disco groove in the song “Night Fever” by the Bee Gees. This groove incorporates a hi-hat pattern with two hi-hat openings and some sixteenth notes. You can hear this beat right at the beginning of the song. (Q=110 BPM)

Start with the hi-hat pattern.

Now, add in the snare drum on beats two and four.

To complete the groove, play steady quarter notes on the bass drum.

This is the most popular disco groove played by drummers. (Q=120 BPM)

Tony Thompson performed this groove in the famous disco song “Le Freak” by Chic. This groove is unique because there are two consecutive hi-hat openings played in a row. Check it out in the recording at 0:34. (Q=129 BPM)

Here’s another sixteenth note groove that incorporates hi-hat accents instead of hi-hat openings. (Q=110 BPM)

In this example, the hi-hats are only played on the upbeats. (Q=120 BPM)

Omar Hakim plays this more challenging disco groove in the song “Get Lucky” by Daft Punk. This groove features a much more syncopated bass drum pattern than the previous examples. You can hear him play it in the recording at 3:26. (Q=117 BPM)

Here are ten of the most iconic disco songs ever recorded. Every drummer should know them! The grooves in these recordings are played by legendary session drummers like Omar Hakim, John “JR” Robinson, and James Gadson. When you listen to and play along with these recordings, focus on the essential elements of disco drumming: hi-hat patterns with accents or hi-hat openings, “four on the floor” bass drum patterns, and consistent backbeats on beats two and four.

The soul and funk grooves that you learned in this chapter incorporate syncopation, displacement, cross-sticking, hi-hat openings, “four on the floor” bass drum patterns, and much more. When you’re playing soul and funk music, it’s important to be able to identify which concepts relate to each specific genre—and to know how they’re applied within different grooves.

Even though the roots of soul and funk music are very closely related, soul and funk drumming are quite different from one another. Soul music is not a drum-focused style of music; the drums simply play a supporting role in the music. On the other hand, funk music is a drum-focused style of music. In this style, you have more freedom to experiment with complexity and embellishments.

You can apply the concepts you learned in this chapter to the grooves you play in other styles of music. These concepts are universal; they’re not limited to soul and funk drumming. If you want to expand on any of the concepts demonstrated in this chapter, you’ll find exactly what you’re looking for inside the members-only area of Drumeo.

Here’s a Spotify playlist of all the recommended songs from this guide:

Did you enjoy this chapter from The Drummer’s Toolbox? To check out the other chapters (and dozens more styles in amazing detail) pick up a copy of the book! You’ll also get a link to a resource center full of additional videos, PDFs, and other content that complements and expands on the book’s material.

Brandon Toews is an author, educator, and performer based out of Vancouver, Canada. Brandon is the author of The Drummer's Toolbox, co-author of The Best Beginner Drum Book, and the Content Director at Musora, home to the award-winning online music education platforms Drumeo, Pianote, Guitareo and Singeo.

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »